For half a century, Keiji Haino has treated sound as an act of resistance. His music—whether molten free improv or ear-splitting noise rock—has always been a revolt against the mundane, an attempt to transcend everything that felt too easy, too neatly resolved. As a teenager in late-’60s Japan, he looked at the counterculture and saw nothing radical at all. The Beatles’ declarations of love and peace struck him as shallow; the revolution, he believed, demanded something far less comfortable. “What I wanted to do and how I wanted to do it was totally different from The Beatles and their ilk,” he once said. His life’s work has been a search for that difference—for an art that could feel truly new, not in style but in spirit. “I want to live each and every moment at its best and to the fullest,” he explained decades later. “To regret is to repeat.”

And yet, on U TA, his latest collaboration with composer Shuta Hasunuma, Haino sounds more at peace than ever before. Known for volcanic performances that seem to scrape at the edges of existence, the Japanese avant-rock icon here contributes only his voice, leaving the instrumentation to Hasunuma’s weightless pianos, synths, and textural flourishes. It’s a startling inversion: the man who once sounded like the end of the world now sounds like he’s watching the sun rise after it.

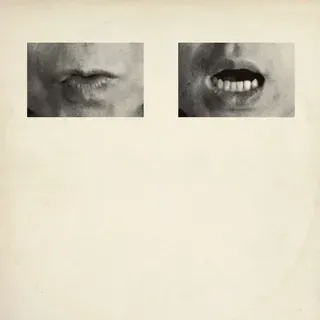

Recorded in the wake of a 2021 live performance, U TA isn’t an attempt to replicate that improvisation, but to reimagine it in studio light. Haino entered with nothing but words, no sense of what his collaborator would play. Hasunuma responded with restraint—soft electronics, vaporous piano chords, a fragile stillness—and Haino adapted in kind. On opener “Sky,” his whistling drifts like wind through glass, before he murmurs poetry that sounds carved from air: “Broken pieces of me / becoming dust of light / falling upon the earth below.” You can hear him swallow, breathe, clear his throat—the body behind the myth, unguarded. For once, his voice isn’t a weapon or a wound. It’s simply human.

Across U TA, Haino’s singing becomes an instrument of intimacy. “Number” stretches his phrasing into long, aching sighs, the notes hovering over Hasunuma’s digital droplets. The effect recalls Ryuichi Sakamoto’s crystalline minimalism or the blurred reverie of Nuno Canavarro’s Plux Quba—music that finds transcendence in tenderness. Elsewhere, “Pause” unfurls like a meditative field recording, the chirping of birds folding into ambient haze. “Drops of overflowing smiles are falling” is pure sound poetry, Haino layering his own voice until it dissolves into texture. It’s a reminder that even his most abstract instincts can yield something luminous when met with care.

Hasunuma, too, seems transformed by the partnership. His solo work often leans toward the whimsical—cartoonish melodies and pastel synths—but here, he resists the urge to overdecorate. Instead, he listens. On “People,” his piano chords shimmer like water, and when Haino murmurs, “I want to bring our powers together,” the moment feels both literal and metaphysical: two artists, generations apart, meeting in stillness. Even when Hasunuma indulges his sweeter tendencies—the pinging synths of “Rest,” the gentle clatter of “Latency”—Haino’s voice keeps the music grounded, tethered to something raw and real.

The surprises are subtle but striking. “Finger” creates a cavernous space, Haino’s vocals bouncing off invisible walls. “Gush” erupts in metallic clangs and static, a reminder that peace doesn’t have to mean passivity. But the album’s greatest revelation is its gentleness: Haino’s ability to surrender without losing intensity. He once sang as if to obliterate everything outside himself; now he sings to merge with it.

In one of his old interviews, Haino described singing as “a way to become one with someone outside of myself.” On U TA, that desire finally feels fulfilled. It’s not the fury of connection, but its quiet hum—the sound of two artists dissolving their edges until what remains is pure presence. For an artist long defined by noise, Keiji Haino has never sounded more alive in silence.