Wolfgang Voigt has always existed in his own orbit—one of electronic music’s most distinctive and quietly transformative figures. Growing up in Cologne, he absorbed the glitter of glam rock and the haze of psychedelics in Königsforst before acid house came along in his late 20s, realigning his life around the hypnotic thud of the bass drum. Under aliases like Mike Ink, he became a central force in Germany’s rave underground, releasing countless EPs that helped define a new techno sensibility. When Voigt co-founded Delirium, the record store that evolved into the Kompakt label in 1993, he and his peers laid the groundwork for the minimalist, melodic strain of techno that would dominate the 2000s.

By the mid-’90s, though, Voigt’s work began to soften at the edges. Sampling experiments with the Roland W-750 led him to blend high and low art—Bee Gees melodies, Roxy Music glamour, and the harmonic dissonance of composers like Schoenberg—into a uniquely European synthesis. His music began to suggest a strange emotional truth buried beneath modern culture’s surfaces, echoing through forests both literal and metaphorical. Projects like Las Vegas (with Jörg Burger as Burger/Ink) bridged the gap between rock and rave, earning a U.S. release on indie powerhouse Matador. His ambient project GAS, constructed from orchestral samples and vinyl hiss, became a cornerstone for generations discovering ambient music. Even the lurching “schaffel” beat—Kompakt’s signature 12/8 rhythm inspired by glam rock and oompah swing—spilled into pop culture, leaving traces everywhere from Goldfrapp to Kanye West.

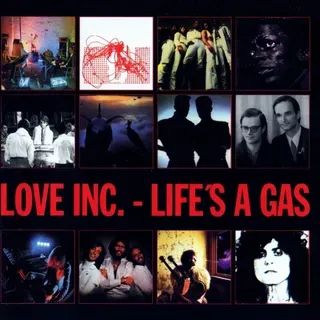

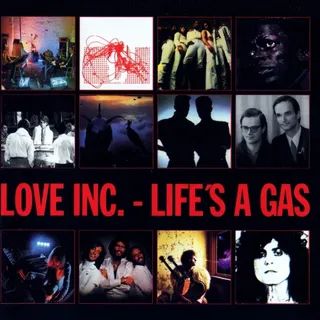

At the heart of Voigt’s vast web of references lies Life’s a Gas, his 1996 album as Love Inc.—a radiant, melancholy love letter to sound itself. Though modestly received upon release, it remains one of Voigt’s most revealing works. Out of print and absent from streaming (likely due to its liberal use of samples), the album literally wears its influences on its sleeve: its cover collages iconic LPs like In a Silent Way and Avalon, signaling a devotion to the lineage of listening.

The record opens with two remixes of T. Rex’s “Hot Love,” the glam-rock anthem that helped ignite a cultural revolution when Marc Bolan shimmied through Top of the Pops in 1971. Voigt, then just a child, seems to have internalized its swaggering shuffle—the 12/8 rhythm that would later pulse through Kompakt’s DNA. His “Mike Mix” of “Hot Love” feels like a lucid dream of adolescence, stretching Bolan’s ecstatic groove into infinity. The GAS Mix, by contrast, buries the original’s glitz under a dense shroud of bowed strings and vinyl fog—transforming glam into something spectral, as if Bolan’s glitter had turned to dust drifting through Voigt’s forest.

The album’s title track reveals Life’s a Gas as both homage and transmutation. Sampling T. Rex’s refrain and looping it over a fragment of Roxy Music’s “True to Life,” Voigt conjures a space where memory and melody dissolve into atmosphere. Long before vaporwave, he was dissecting nostalgia, turning pop’s fleeting pleasures into ghostly, reflective textures.

Released in two versions—vinyl and an extended CD edition—the record straddled the border between techno and art rock. The vinyl leaned into the dancefloor, with acid-driven cuts like “T.R.I.B.U.T.E.,” while the CD expanded into lush, cinematic detours. Tracks like “Where It’s At” and “Lady Democracy” flirted with downtempo sensuality and ironic grandeur, their samples (including a reimagined Queen ballad) reframed as acts of reverence rather than theft. As Voigt once said, “You find something great—you want to connect to it and preserve it.”

In hindsight, Life’s a Gas predicted the fusion of electronic and rock aesthetics that would soon define acts from Daft Punk to Justice. Its textures anticipated both the soft-rock nostalgia of the 2000s and the widescreen melancholy of modern ambient techno. Voigt proved that dance music could channel the emotional weight of classic rock while erasing its ego, distilling feeling to its purest form.

Nearly three decades later, Life’s a Gas stands as a Rosetta Stone for understanding how electronic music absorbed the glamour, melancholy, and romantic sweep of 20th-century pop. Across its 72 minutes, Voigt sustains the illusion of a perfect song—then dissolves it, leaving only the glow that lingers after the music fades.