I’m not old enough to remember when rap was a community project. For my generation, hip-hop was less a cipher and more a selfie: the art of constructing an “I” loud enough to drown out everything else. We came of age on the gospel of self—self-preservation, self-aggrandizement, self-promotion. If you were young and searching in the late 2000s, it didn’t take long to get converted: one bar about Winn-Dixie bags full of money and you were baptized. The message barely mattered. What mattered was swagger—the ability to make your existence sound bulletproof through blown-out speakers. Hip-hop wasn’t about saving the world anymore; it was about soundtracking your reflection.

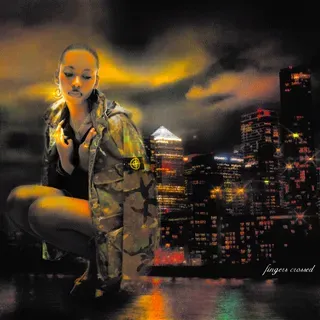

kwes e, a Ghanaian-British artist in his twenties, seems to understand that impulse instinctively. His new album fingers crossed is built on that same architecture of affirmation—part jerk-rap, part alté, part R&B—and it’s meant to feel good first, profound second. He’s made it, so he flexes: day trips to Paris, diamond skin, champagne visions. But when the serotonin kicks in, he’s electric. “lyk,” his Afrobeats-soaked club breakout, feels like lightning in a tequila bottle, a song so confident it makes the air crackle. The beat flips a syrupy synth line straight out of Lil Wayne’s “Lollipop,” while kwes e rides the groove like a veteran flirt, his delivery equal parts silk and static. But it’s “fela kuti,” fingers crossed’s moral and musical centerpiece, that hits hardest—a loose homage to the Pan-African icon that threads ancestry into flex culture. “Ro-ro-ro-rock star like Fela,” he chants, his tone somewhere between tribute and self-invention. In an era where political urgency often feels performative, there’s something quietly radical about a pop-rap kid linking his lineage to one of the continent’s fiercest revolutionaries.

Not every track earns that gravity. fingers crossed wants to be an event—the sound of a new name claiming its glow-up—but the spectacle often outpaces the storytelling. kwes e sets the scene like a movie trailer: “City lights in my face, nothin’ better,” he croons on the opener, Auto-Tune glimmering like diamonds in the dark. But too often, the specifics dissolve into platitudes. You can hear the aspiration—Meek Mill’s hunger, Travis Scott’s texture—but not the nuance that makes the hunger believable. The flexes blur together: Margiela, double Gs, empty luxury as shorthand for fulfillment. “I got money girl, so I’m happy now,” he sighs on “addicted to divas.” But what does that happiness sound like? The dream is rendered in logos, not details.

Still, even when the writing falters, the lineage keeps pulling him back toward something real. “wishes” glides on a wistful jazz shuffle; “entitled” sneaks in the pulse of a digital djembe. The Afro-diasporic undercurrent—the soft insistence of rhythm, the unbroken link between groove and identity—anchors the record’s slick pop edges. When he locks in, he’s incandescent: “dorothy in red margielas” struts with the same confidence as “fela kuti,” while “7am” is his most sumptuous moment yet, a plush R&B reverie with Miami bass bones and feathery harmonies that shimmer like sunlight through tinted windows.

kwes e’s debut is less about revelation than evolution: a young artist learning how to balance the myth of self with the memory of a collective past. He’s not Fela, and he doesn’t have to be. But every time he slips a little history into the heat of his hedonism, you can feel the music inching closer to something generational. To borrow from Fela himself, “music is the weapon.” kwes e is still learning how to aim.