The jazz-punk polymath opens the floodgates, turning decades of groove, grit, and digital noise into radiant color.

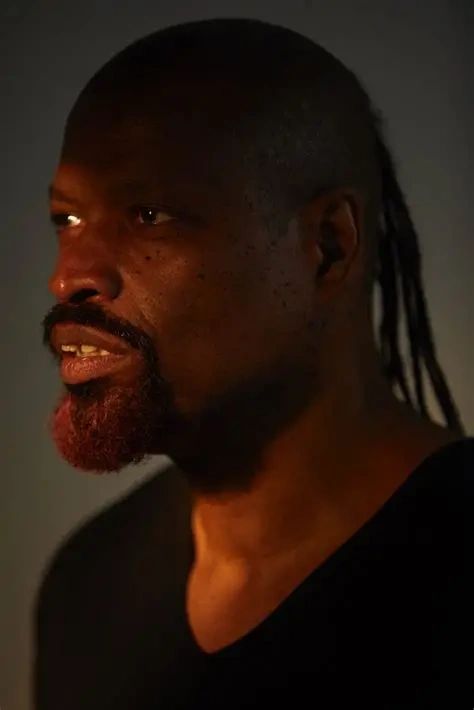

Venture far enough into the borderlands of jazz-punk, harmolodic funk, and downtown skronk, and you’ll eventually run into Melvin Gibbs. The Brooklyn bassist has been a connective tissue of American experimental music for more than four decades—a conduit between no wave’s urban chaos, hip-hop’s rhythmic defiance, and jazz’s boundless elasticity. In the early ’80s, he held down the low end in Defunkt, the nervy New York band that fused punk energy with horn-section bombast. Since then, Gibbs has played alongside Vernon Reid, Sonny Sharrock, John Zorn, Bill Frisell, and Henry Rollins, his basslines threading through the DNA of countless scenes that never bothered with boundaries.

In 2022, his Anamibia Sessions 1: The Wave—one of the final projects released by the late Peter Rehberg on Editions Mego—sank deep into the subterranean. A textural labyrinth of bass drones and reverberant fog, it felt like a transmission from the ocean floor, somewhere between Thomas Köner’s ghostly ambient minimalism and Sunn O)))’s molten doom. Its follow-up, Amasia: Anamibia Sessions 2, feels like the inverse—a record that bursts upward and outward, shedding darkness for prismatic light.

If The Wave was a collapse into the void, Amasia is the explosion that follows. Released on Hausu Mountain, the album finds Gibbs reimagining his language in full color, weaving funk, jazz, and digital psychedelia into something dazzling and unpredictable. The spirit of ’70s Miles Davis hovers over the record—particularly the electric sprawl of On the Corner and Agharta—and Gibbs honors that lineage by including recordings with Pete Cosey, Davis’ pyrotechnic guitarist and one of Jimi Hendrix’s spiritual heirs. Yet Amasia doesn’t mimic that analog excess; it refracts it through a distinctly 21st-century filter. Where The Wave was monolithic, Amasia is pointillist—closer to the glitchy sprawl of Brainfeeder’s more alien output or the hyper-synthetic prog of Hausu Mountain’s own catalog. At times, the record sounds like what might happen if Timbaland and Thundercat locked themselves in a studio and decided to make free jazz for cyborgs.

Despite its scattered origins—the material spans nearly two decades—Amasia coheres into a seamless 38-minute arc. “Felonious Monk” opens with a rhythmic sleight of hand, Gibbs’ bass sliding through a beat that shapeshifts from Brooklyn drill to the frenetic pulse of Ghanaian producer DJ Katapila. “Gullah Jack Style,” featuring Cosey’s snarling guitar, flips Curtis Mayfield’s “Pusherman” into a skittering liberation groove. On “The Very First Flower,” gentle cymbal splashes bloom into electric-piano petals; it’s Gibbs at his most serene. “16 Dimensions of Underwater Light,” co-written with trumpeter Chris Williams, stretches that calm into abstraction—suspended drums swinging like pendulums over a submerged hum, as if you’re hearing the echo of a club night from beneath the waves.

Then comes “Luigi Takes a Walk,” the 13-minute centerpiece that fuses ecstatic jazz propulsion with swampy funk drag. With Greg Fox (of Liturgy and Body Meπa) on drums, the track starts as a spiritual jazz sprint before melting into a drunken, prehistoric groove—like a mastodon trying to dance. Gibbs’ bass is at its thickest here, growling and grinning at once. The closing “O.G. Dreams of Lost Love” collapses into eerie ambience, its blown-out woodwinds and beatboxed percussive burps writhing like small mechanical creatures in the debris field.

For an artist now in his late 60s, Amasia feels startlingly contemporary—not as an attempt to “keep up” but as proof that Gibbs was already there. His music has always treated genre as raw material rather than destination, and here he channels the hyper-digital language of modern experimentalism without losing his sense of funk, community, or mischief. The result is both a personal summation and a reanimation: the sound of an elder statesman reminding everyone that the avant-garde was never supposed to sound safe.

Amasia also marks a small triumph for Hausu Mountain, a label better known for vapor-bright noise and absurdist electronic music than for elder jazz-punk deities. Taking the torch from the late Editions Mego, HausMo turns Gibbs’ lifelong conversation with rhythm and resistance into something vividly of-the-now. If The Wave was the descent, Amasia is the rebirth—a technicolor resurrection of one of America’s most quietly revolutionary musicians.