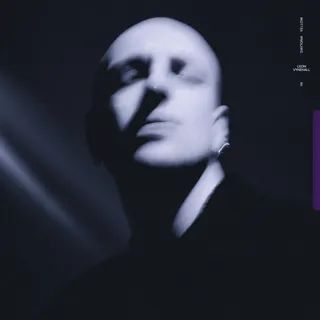

Leon Vynehall has always been a producer who thinks through sound. Over the past decade, the British artist has built a reputation for crafting albums that double as conceptual blueprints—records accompanied by essays, films, and sprawling liner notes that invite listeners inside his mind as much as onto the dancefloor. Even at his most accessible, like on 2021’s Rare, Forever, Vynehall wrestled with how much explanation his work required. Halfway through “Dumbo,” he even broke the fourth wall to ask, “Dya know what I mean?”—as if uncertain whether the music alone could carry the message. His new album, In Daytona Yellow, is his answer to that tension: a messy, self-aware, and deeply human record about letting go of control. It’s the sound of an artist intentionally loosening his grip—and sometimes losing his footing in the process.

One of the album’s biggest shifts is its embrace of the voice—not just as texture, but as central instrument. Vynehall enlists a cast of vocalists who lend his productions a new emotional dimension, transforming his meticulous sound design into something warmer, riskier, and more intimate. He joins them, too, stepping out from behind the console to sing, speak, and recite poetry. The move recalls other producers-turned-frontmen like Matthew Dear or Todd Edwards, but Vynehall’s approach feels hesitant, even self-conscious. His voice—an unsteady, grainy baritone—often seems tucked behind layers of processing, as though he’s unsure if it belongs in the spotlight.

The opening track, “Life Is Not Enough,” captures this uneasy vulnerability. What begins with buoyant synth stabs and pulse-quickening percussion soon gives way to a wash of strings and Vynehall’s hushed, digitally treated vocals. It’s haunting and beautiful, but his delivery wavers between sincerity and guardedness. The pitch correction that cloaks his voice feels less like a stylistic flourish than a kind of armor. When Vynehall steps aside, his collaborators thrive. On “Mirror’s Edge,” POiSON ANNA’s voice curls around the beat like smoke, turning casual flirtation into existential inquiry: “What does it mean when I need you? / Who do you call in despair?” The song erupts into a rush of orchestral static before surging back to life, its chaos both thrilling and cathartic. Similarly, “Cruel Love,” featuring Beau Nox, trades groove for volatility—its structure bending and breaking as Nox’s desperate refrains give way to a storm of distortion.

Elsewhere, the album’s quieter moments don’t always sustain the same intensity. The mournful “You Strange Precious Thing,” featuring Chartreuse, trudges toward an anticlimactic breakdown, its emotional potential left unrealized. “Scab,” with TYSON, rides a buoyant rhythm and breezy vocal, but drifts without direction. Throughout In Daytona Yellow, Vynehall’s fingerprints remain visible—his knack for intricate percussion, textural depth, and compositional detail—but the record’s collaborative sprawl sometimes dilutes his perspective. What once felt like precision can, here, blur into restlessness.

.jpeg/:/cr=t:0%25,l:0%25,w:100%25,h:100%25/rs=w:1280)

Yet, that disorientation may be the point. In Daytona Yellow frames its stylistic sprawl as a metaphor for Vynehall’s internal struggle: the battle between identity and adaptability, perfectionism and freedom. Midway through “Whip,” a sampled voice reflects, “We develop our personality based on what’s around us… and so that means we cut off a part of ourself.” The line hovers over the album like a thesis statement. Vynehall’s recurring poem begins with the plea, “Forget your perfect offering,” echoing Leonard Cohen’s “Anthem” and its faith in imperfection as the only path to transcendence.

By the time the closing track, “New Skin Old Body,” arrives, Vynehall seems to have surrendered to that imperfection. His processed voice loops through the haze, repeating, “I am a strange loop,” until the phrase collapses under the weight of noise and static. It’s a fitting metaphor for the record itself: recursive, flawed, and searching.

In Daytona Yellow doesn’t aim for perfection—it dismantles it. In doing so, Vynehall delivers one of his most vulnerable and confounding works yet: an album where chaos becomes catharsis, and self-exposure becomes its own kind of liberation.