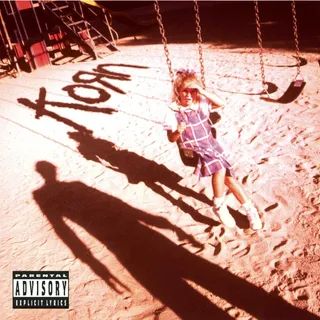

The sobs are real. About five minutes into “Daddy,” the final track on Korn’s 1994 debut, the band surges back after a low, trembling pause. It’s the intended climax—a moment where Jonathan Davis is supposed to finally let go, to scream his way through the memory of childhood rape and the disbelief that followed. But what happens instead doesn’t sound like catharsis. It sounds like collapse. The final chorus dissolves into gasping, wordless sobs; the performance spirals out of control. You can hear the mic clipping, the studio air thickening. Then the tape keeps running, catching Davis weeping on the floor while his band improvises around his unraveling. He mutters, swears, and slams a door. Silence.

It’s still one of the most unnerving endings in heavy music—a moment of naked breakdown that refuses spectacle. For all its extremity, it’s not about shock; it’s about exhaustion. Davis isn’t performing pain, he’s succumbing to it. And yet, that’s the paradox that makes Korn so striking. Even at its most unguarded, it’s a record about what happens when pain becomes performance, when trauma turns into theater because there’s no other outlet left.

At the time, Davis was 23, a former coroner’s assistant from Bakersfield who looked like he’d wandered into the wrong decade of MTV. He wore Adidas track suits and dreadlocks, carried a bagpipe, and sang like someone being torn apart by the contradictions inside his body. His band—guitarists Munky and Head, bassist Fieldy, drummer David Silveria—played with a kind of physical unease, each instrument sounding slightly off-axis, as though trapped between industrial metal and hip-hop but never at peace with either. Together, they stumbled into something new: music that didn’t just express alienation but embodied it.

Even three decades later, Korn still feels like an origin story—messy, awkward, and utterly alive. You can hear Davis inventing a new emotional language in real time: part sob, part snarl, part guttural vowel spill. His phrasing owes as much to hip-hop’s rhythmic breath control as it does to death metal’s roar. He moves from a whisper to a panic attack to something that sounds like he’s speaking in tongues, blurring melody into mania. It’s what makes “Daddy” such a rupture—not just for metal, but for the idea of what a rock frontman was supposed to sound like.

Ross Robinson, the producer who would become nu metal’s Rick Rubin, understood the volatility in front of him. He didn’t polish it; he amplified it. The guitars are down-tuned seven-strings that seem to melt into the mix rather than ride on top of it. The bass grinds and snaps, more percussive than melodic, a subwoofer’s growl turned into human anguish. Silveria’s drums sound impossibly close, like the listener is standing between the toms. The production is claustrophobic, ugly, and vivid—an aesthetic that would define a decade.

When Korn dropped in October 1994, it didn’t fit anywhere. Metal was splintering: Pantera had claimed the throne for aggression, Rage Against the Machine were politicizing the groove, and grunge was collapsing under its own self-serious weight. Korn offered a new blueprint: a music of internal collapse, of rage turned inward. It was groove-oriented but anti-glamour, emotional but not sentimental, a sound that refused to clean itself up.

And yet, for all its heaviness, Korn is startlingly personal. Davis’s lyrics are so blunt and self-lacerating that they sometimes feel like diary entries someone left burning on the floor. On “Faget,” he reclaims the slurs and ridicule of his teenage years, spitting them back with venom until the insult loses its meaning. On “Need To,” he seethes through obsession, confessing desires that sound too raw to control. Even “Shoots and Ladders,” with its mocking use of nursery rhymes, feels like a haunted memory of innocence turned to ash.

The band’s innovation was emotional just as much as sonic. Korn made vulnerability sound violent. Davis didn’t just describe trauma—he weaponized it, transforming his humiliation into confrontation. His delivery made space for a kind of pain that metal had rarely allowed: male fragility, queerness, violation, shame. Before Korn, heavy music largely dealt in power fantasies. After Korn, it could sound like panic attacks.

The result was an album that reshaped the DNA of rock for the next decade. You can hear its aftershocks in Slipknot’s psychodrama, in Deftones’ dreamlike sensuality, in Linkin Park’s digital despair. But none of those bands sounded as precarious as Korn. Even at its most anthemic, the record feels one step away from breaking. Every riff hangs by a thread, every groove threatens to implode. The tension is relentless.

And yet, there’s an undeniable groove to Korn. Fieldy’s bass pops like a heart under pressure, the drums throb with nervous precision, and the guitars drone in jagged, syncopated chunks that almost—almost—swing. It’s the sound of a band that understands funk but rejects joy. The riffs grind instead of groove. The rhythms circle like vultures. Every song feels like it’s clawing toward release but never reaching it.

Even so, the album isn’t humorless. Davis occasionally slips into manic absurdity—the bagpipes on “Shoots and Ladders,” the whisper-scream dialectic of “Ball Tongue.” The record balances self-awareness and self-immolation in equal measure. Korn knew the line between sincerity and spectacle and decided to erase it.

.webp/:/cr=t:0%25,l:0%25,w:100%25,h:100%25/rs=w:1280)

The more you sit with Korn, the clearer it becomes that its greatest innovation isn’t technical—it’s psychological. The record understands that pain can’t be contained by genre. It merges the raw confessionalism of ’90s alt-rock with the rhythmic violence of metal and hip-hop, creating a sound that’s both claustrophobic and liberating. It’s emotional maximalism for the emotionally illiterate: a way to scream when words don’t work.

Listening to it now, it’s hard not to hear Korn as the start of a cultural reckoning. Before nu metal became Hot Topic uniformity—before Limp Bizkit’s frat-rock sneer or Papa Roach’s self-help angst—this was a record about survival without redemption. It didn’t promise healing. It didn’t even promise understanding. It just promised honesty, no matter how ugly it got.

“Daddy” remains its black heart—a song so raw it still feels like you shouldn’t be hearing it. When Davis breaks down, when the sobs choke out the words, it’s not just his story anymore. It’s the sound of repression detonating in real time, of someone finally letting the darkness speak. There’s no outro, no fade-out, no tidy conclusion. Just a man, a band, and the sound of a door slamming on what came before.

Nearly thirty years later, Korn still sounds dangerous—not because of its aggression, but because of its vulnerability. It’s a record that turned pain into propulsion, shame into structure, alienation into art. The sobs are real, and so is the aftermath.