Chris Williams’ Odu: Vibration II is not easily defined. Across six sprawling tracks and nearly 40 minutes, it shapeshifts between drone, improvisation, and ritual. At times, it feels like a group meditation; at others, a séance or lament. The deeper you listen, the less it feels like music and the more it resembles a process of transcendence—an experience of dissolving boundaries, not only between instruments and players but between sound and self.

Williams, a trumpet player and electroacoustic composer, thrives at the intersections of jazz, ambient music, and experimental sound art. His past work—like the 2021 collaboration Sans Soleil with saxophonist Patrick Shiroishi—revealed a fascination with texture and the smallest audible details, turning improvised breath and brass into something almost tactile. In his Remembrance Quartet and on 2022’s Live, Williams leaned into the communal spirit of jazz and groove. But Odu: Vibration II marks a new creative summit: a work that merges deep improvisation, ambient sound design, and raw emotional gravity into one immersive form.

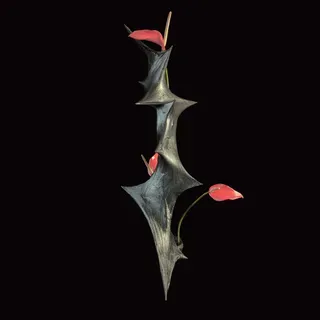

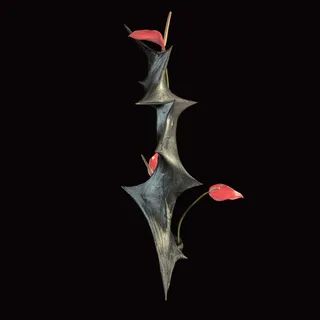

Recorded live at Roulette Intermedium in New York with Shiroishi and trombonist Kalia Vandever, the album hardly feels “live” in the traditional sense. Each instrument is filtered, stretched, and submerged in effects until their origins blur. The result is less a performance than a sonic descent—Williams has called the record a metaphorical journey into a cave, a space both physical and mythic. The album unfolds slowly, like a long camera shot moving into darkness, where sound takes on geological weight.

The opener, “Moon,” begins with a deep, vibrating synth drone and the breathy whisper of a horn. As layers accumulate, faint melodies emerge—tentative, searching, then swallowed by vast reverb. Williams’ trumpet seems to hover above a shifting landscape, joined by the plaintive cries of his collaborators. It’s music that glows and vanishes at the same time. “Visage,” which follows, feels lighter—a study in harmonic interplay, the three horns moving together in slow, glowing motion. The track’s quiet beauty recalls the meditative grandeur of Stars of the Lid or the spiritual minimalism of Alice Coltrane.

But Odu soon unravels. “location.echo” strips everything away until only hissing breaths, scraping textures, and ghostly echoes remain. It’s the sound of losing orientation, as if the listener has ventured too far into the cave. In interviews, Williams has admitted that his fascination with caves is partly rooted in fear—a primal discomfort with darkness and the unknown. That anxiety ripples through the second half of the album, where structure and melody give way to chaos.

“Waning” offers a brief reprieve: Williams’ trumpet floats above field recordings and chiming bells, evoking a fragile peace. But the centerpiece, “Stemmed outwards,” pulls the listener into a storm of distortion and static. For nearly 15 minutes, sounds loop and fracture, like broken transmissions from deep underground. Shiroishi’s saxophone cuts through the noise with a piercing, anguished solo, summoning the raw emotion that underlies the album’s abstraction.

Then comes the release. “Stemmed inwards,” the brief final track, reintroduces calm and harmony—three horns in unison, glowing and clear, as if sunlight has finally reached the cave floor. After the turbulence, the simplicity feels redemptive.

What makes Odu: Vibration II extraordinary is not its technical ambition but its sense of passage. Williams doesn’t just craft an ambient record; he builds an emotional journey through fear, disorientation, and renewal. The album’s darkness is real, but so is its light. In the end, it feels less like a performance and more like a shared act of survival—a reminder that even in the deepest spaces of sound and silence, we are never alone.