December 03, 2025|Review

Shortly before releasing their debut, last year’s No Glory, Hannah Pruzinsky did something that feels almost mythic in the era of side hustles and creative compromise: they quit medicine—an entire white-coated future—in order to chase the fragile, flickering promise of songwriting. Within months, they’d become a familiar face in New York’s DIY constellation, sharing cramped stages with Florist and the Ophelias, trading gear and poems, and co-founding GUNK, a zine that feels like a time capsule from when scenes still mattered. As h. pruz, Pruzinsky writes with the quiet authority of someone who’s already burned their lifeboats. No Glory was a love record in the classic sense—wide-open, starry-eyed, brimming with the assurance that choosing love and choosing art were the same gesture.

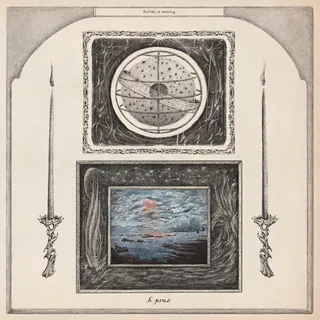

Red sky at morning arrives from the moment after that certainty evaporates. It’s the sound of someone waking up beside the person they love and realizing that devotion, like weather, can darken without warning. Pruzinsky grounds that revelation in hushed, amber-toned folk before allowing it to be swallowed by something stranger, dreamier, and intermittently grotesque.

By track two, the façade is already cracking. “Arrival” is pitched as “domestic bliss… teetering on the edge of insanity,” and the phrase isn’t hyperbole. “We haven’t left the house in weeks,” Pruzinsky marvels, as if realizing too late that comfort and confinement often share a border. They try to outrun old habits, only to feel them crawling back: “Let the past coat my lungs/They said the tissue would rot out/But I know that my thoughts are good.” It’s the album’s thesis in miniature—love can be sturdy, but dread has a way of leaking through the drywall.

“After Always” masquerades as a devotional, but the instrumentation betrays its unease: Felix Walworth’s rhythm tiptoes around the lyrics like someone afraid of waking a sleeping body, and Jonnie Baker’s bass creeps as if mapping escape routes. The line between surrender and suffocation has rarely sounded so thin.

The record glows darkest where Pruzinsky lets their imagination metastasize into full-blown myth. The physical release arrives with a surreal RPG-style booklet—illustrations tracing a sailor’s descent into their own psyche—and suddenly songs like “Force” and “Krista” read like dispatches from that inner world. “Krista,” buoyed by Walworth’s National-esque drum bursts, plays like a gothic campfire story whispered in the daylight: unheard screams, half-seen apparitions, intimacy blurred with haunting.

As on No Glory, Pruzinsky drops the curtain for one distorted rupture. “If you cannot make it stop” detonates like an overdriven panic attack, fizzling apart as they confess, “I keep on thinking of defeat.” It’s a thrilling derailment, a reminder that beneath the album’s warmth lies a volatility waiting to spark.

Walworth’s production keeps everything close—breath-level, handheld, glowing like the last lamp left on in a house late at night. Even the interludes, featuring Skullcrusher’s Helen Ballentine, drift in like fog between thoughts. They don’t push the record forward so much as thicken its atmosphere; a dream needs its vapor.

The collaborative spirit that sustains New York DIY flickers at the album’s edges. Emily A. Sprague’s Buchla solo on opener “Come” unspools like a galaxy forming, while Al Carlson’s sax drifts through like a half-remembered conversation. “Your Hands,” with features from Pruzinsky’s Sister bandmates and Sprague’s Florist collaborator Rick Spataro, is the album’s most communal moment. Even as Pruzinsky sings about psychic distance—“Sclera red, psychic pain, my head’s in the other room out of reach”—the arrangement lifts the song into something reassuring, almost luminous. Trust becomes the album’s quiet counterweight: “Yes, baby, you wouldn’t lie to me/Baby, you always try with me.”

Red sky at morning understands that love doesn’t lose its meaning when the fear creeps in; it simply becomes more complex, more adult, more lived-in. Pruzinsky isn’t mourning the end of a honeymoon—just learning how to stay when the weather changes.