What do you see when you hear the word “Chicago”? Maybe the skyline first—steel towers piercing the clouds, a glint of glass against gray skies. Maybe the food: mustard-drenched hot dogs, beef sandwiches slick with jus, deep-dish pizza so heavy it feels like an act of endurance. Maybe it’s Jordan’s tongue-out jump shot or Harry Caray’s ecstatic rasp. But for the people who actually live there, the city isn’t just icons and postcards—it’s the lake. Cold, endless, grounding.

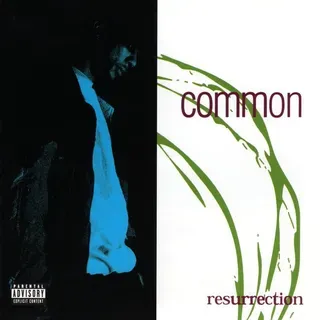

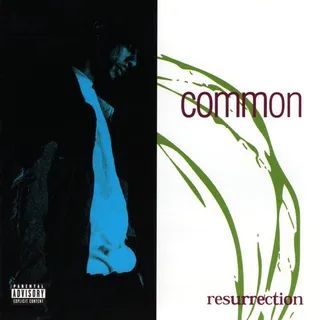

That lake gleams on the face of Resurrection, Common’s 1994 album that feels like a love letter written in longhand to his hometown. Printed right onto the disc is an image of the sun rising over Lake Michigan—a perfect visual metaphor for an artist growing into his own clarity. At 22, Lonnie Rashid Lynn, still calling himself Common Sense, was learning how to translate the pulse of Chicago—the humor, the melancholy, the rhythm of its neighborhoods—into music that could breathe.

The leap from Can I Borrow a Dollar? to Resurrection is like watching a man shed a costume. The debut had the posture of early ’90s East Coast hip-hop but none of the identity; all muscle, no marrow. By Resurrection, Common was no longer performing “being a rapper”—he was narrating what it meant to be from somewhere. His South Side came alive in flashes: biking through parks, cruising Lake Shore Drive in a dented Celica, stopping by corner stores and beaches that felt like second homes. These weren’t just details—they were coordinates in the emotional geography of Chicago’s Black youth.

A lot of that transformation came from No I.D., the quietly brilliant producer who rebuilt the album around dusty jazz samples and the patience of a man who digs until dawn for a perfect loop. His beats gave Common’s reflections a body—warm, resilient, full of ache. Together, they created a sound that blurred lines between hip-hop, soul, and introspection. Instead of rapping at the listener, Common was rapping through something—like a poet learning how to breathe in meter.

On “Resurrection,” the title track, he practically narrates his own evolution: “Proceed to read and not believing everything I’m reading.” His voice deepens; his confidence steadies. He talks about quitting malt liquor, about seeing clearer, thinking sharper. It’s a spiritual reawakening disguised as a rhyme.

Across the album, Common toggles between loose-limbed freestyles (“Watermelon,” “Orange Pineapple Juice”) and moments of quiet reckoning (“Book of Life,” “Thisisme”). The genius of Resurrection isn’t in any grand statement but in its tone—a balance of swagger and sincerity that feels distinctly Midwestern. No I.D.’s production keeps things grounded, wrapping Common’s bars in the warmth of Ahmad Jamal piano loops, Freddie Hubbard horn lines, and Mista Sinista’s turntable punctuation. It’s a love language composed of crackles and swing.

Then there’s “Nuthin’ to Do,” the record’s emotional axis. On paper, it’s just a day-in-the-life story, but underneath, it hums with longing. Common sketches the idle afternoons of adolescence—bikes, girls, radio shows—and slips in a line that hits like a cold wind: “But the shit ain’t as fun now, and the city’s all run down.” It’s not just nostalgia—it’s grief for a city devoured by neglect, violence, and headlines that reduced neighborhoods to statistics. Against No I.D.’s mournful saxophone, the song becomes a quiet act of preservation: a refusal to let joy be stolen from the narrative of the South Side.

By the time “I Used to Love H.E.R.” rolls around, Common has figured out how to turn metaphor into manifesto. The “her” in question, of course, is hip-hop—a once-vibrant lover now corrupted by industry and imitation. It’s brilliant, yes, but also the kind of brilliance that invites argument. Ice Cube took it personally, fired back with venom, and Common responded with “The Bitch in Yoo,” a diss so precise it nearly erased the West Coast–East Coast divide for a moment of sheer verbal carnage.

When the dust settled, Resurrection didn’t dominate charts—it sold modestly—but it changed how people heard Common. He was no longer just another rapper from nowhere; he was a Chicagoan with vision, bridging Curtis Mayfield’s spiritual introspection and A Tribe Called Quest’s cerebral groove.

Within a few years, he’d drop the “Sense,” move to New York, join the Soulquarians, make mistakes, date celebrities, win awards, and become something like a cultural elder. But Resurrection remains the hinge—the moment when he stopped trying to fit in and started to sound eternal.

Every morning, the sun still climbs over Lake Michigan. And somewhere in that reflection, Common’s voice still echoes—measured, grateful, reborn.