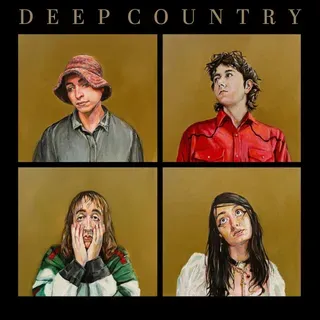

The Albany quartet stretch time until it melts, turning a 75-minute folk odyssey into something that feels infinite.

During the CD boom of the ’90s, the compact disc promised liberation—more minutes, more fidelity, more room to sprawl. Artists took the bait. No longer hemmed in by the physical limits of vinyl or the hiss of cassette tape, tracklists ballooned into double-album dimensions. That same impulse resurfaced two decades later when streaming broke the dam again. With Spotify and Apple Music paying out by the play, and Billboard rewarding length with chart advantage, artists learned to roll out 20-track monoliths like red carpets—each extra song another lottery ticket for virality.

Somewhere in that inflationary spiral, the long album stopped feeling generous and started to feel strategic. Length became a marketing metric, not a canvas. So when a record dares to run past the hour mark in 2025, it needs to earn it—to justify every minute with a world worth inhabiting. On Deep Country, Bruiser and Bicycle take that challenge personally.

The Albany quartet—Keegan Graziane, Nicholas Whittemore, Zahra Houacine, and Joe Taurone—treat time not as a constraint but as a playground. Their third album clocks in just shy of 75 minutes, yet it never drags. Instead, Deep Country drifts, glides, and ambles with the unhurried curiosity of a daydream. It’s an album less concerned with propulsion than with expansion—each song a small world with its own weather system.

Where 2023’s Holy Red Wagon overflowed with kinetic prog-pop energy, Deep Country exhales. Its opener, “Dance and Devotion,” begins with a single, hesitant guitar, each note like a stone dropped into still water. From there, the band wanders—sometimes barefoot, sometimes delirious—through freak-folk waltzes and lo-fi carnival jams. “Silence, Silence” twinkles with glockenspiel and whispers, “21st Century Humor” pounds like a parade assembled from plastic buckets, and “O’ There’s a Sign” melts between arpeggiated guitars and trembling synths.

What’s remarkable isn’t the variety but the patience. Bruiser and Bicycle move at the speed of thought, giving every sound room to shimmer and dissolve. When hooks arrive, they feel like gifts—rare blooms in a meadow of improvisation. Deep Country plays like the Beach Boys’ Smile sessions, if they’d been recorded in an upstate barn after a collective acid nap: one part baroque pop, one part slacker-folk, two parts Elephant 6 séance. “Syd Barrett’s Disaster Picnic” and “Slow Motion Beauty” make good on the title’s promise, dissolving form into a blissful soup of harmonies, strings, and gentle chaos.

All four members sing, often at once, weaving harmonies that sound more communal than composed. Their voices wobble, collide, and laugh together—more potluck than choir. On the title track, they yell “woo!” like kids on a rollercoaster; on “Part of the Show,” bah-bah-bahs tumble out like confetti. It’s the kind of looseness that feels earned, never careless. “Waterfight” distills that energy best—part Animal Collective at their most human, part campfire jam where the fire’s long gone out but no one’s ready to sleep.

Depending on your appetite for sprawl, Deep Country’s length is either its flaw or its freedom. “Get to the point,” Whittemore chants on “Million, Million,” half-mocking the idea that there is one. But Bruiser and Bicycle’s point is precisely the lack of urgency. The album invites you to unlearn impatience, to live inside its unhurried logic. By the time “Sinister Sleep Shuffle” dissolves into jazzed-out cymbals and murmuring bass, time itself feels elastic.

Deep Country doesn’t just stretch the album form—it rehabilitates it. In an era where long tracklists too often feel like content dumps, Bruiser and Bicycle remind us that excess can still mean abundance, and that there’s beauty in getting lost.