Bruce Springsteen was right all along. The definitive Nebraska—the one that continues to haunt American songwriting like a flickering ghost light—wasn’t forged in some mythic studio with the E Street Band, nor conjured through million-dollar mixing consoles or marathon sessions. It was born in isolation, on a winter night in 1982, in a modest Colts Neck, New Jersey home: just a man, an acoustic guitar, a TASCAM PortaStudio, and an Echoplex, tracking rough demos for what he assumed would become his next full-band record. Those demos, of course, were the record. Four decades later, Nebraska 82: Expanded Edition doesn’t overturn that fact so much as illuminate the extraordinary tension beneath it. Everything that followed—every experiment, every attempt to electrify or expand the songs—was a fascinating detour around a truth Springsteen already knew instinctively: that sometimes the tape catches everything it needs to the first time.

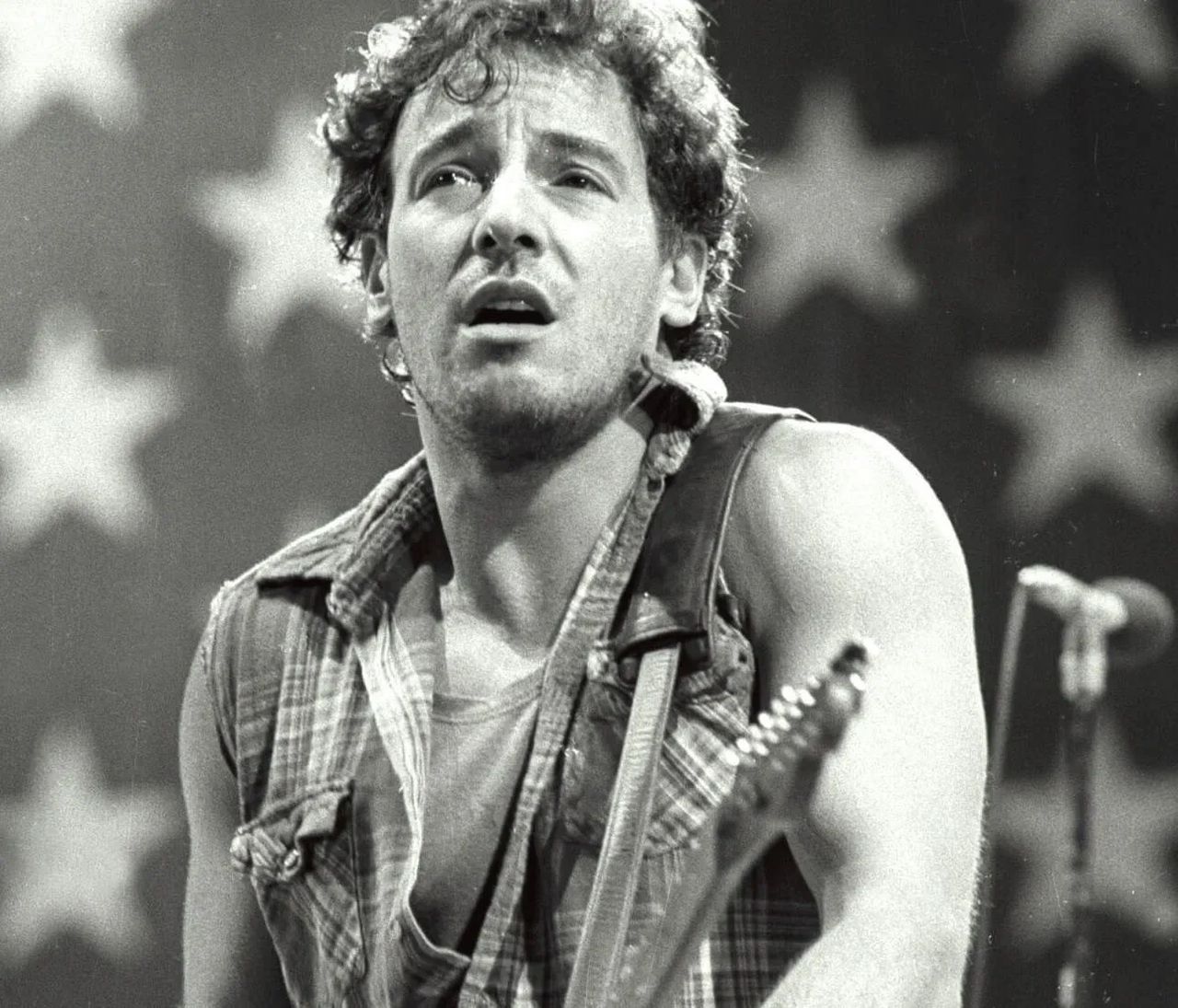

Still, what an experiment it was. In the early ’80s, Springsteen had the wind of success at his back. “Hungry Heart” had broken him onto the pop charts, The River had solidified his stature as the nation’s scruffy poet laureate, and the road had become his second home. But instead of basking in triumph, he drifted toward something darker—songs about dead ends and moral exhaustion, stories where the American dream curdled into guilt and silence. He wrote Nebraska in a fever, intending to flesh it out later with the E Street Band. The resulting tapes, so stark and haunted, ended up being the finished album. There was no press blitz, no tour, just a man and his ghosts.

That decision—born out of creative restlessness and an almost ascetic commitment to truth—paved the road to his commercial explosion two years later with Born in the U.S.A. In between, Springsteen shed and reimagined entire records’ worth of material, much of which now surfaces in various forms across Tracks and Tracks II: The Lost Albums. He co-wrote for Gary U.S. Bonds, gifted Donna Summer a Grammy-winning single, and bulked up both physically and sonically. To outsiders, it looked like a golden era. But inside the storm, Springsteen felt trapped in a cycle of doubt and dislocation—the kind of existential stall that only becomes mythic in hindsight, or once Hollywood casts Jeremy Allen White to play you.

Nebraska 82: Expanded Edition unpacks that paradox with clarity and awe. It’s not just a remaster—it’s a time capsule cracked open. The box collects the original album, polished subtly to reveal new dimensions of its lo-fi architecture; a disc of acoustic outtakes that share its desolate grace; the long-rumored Electric Nebraska sessions; and a newly filmed performance of Springsteen playing the record solo in an empty New Jersey theater earlier this year. It’s both an archival deep dive and an act of preservation: a reminder that simplicity can hold enormous sophistication. Listen to the remastered “Atlantic City” on headphones and you’ll hear it—the delicate unraveling of guitars, mandolin, and backing vocals in the final 30 seconds, each fading out like lights along a boardwalk. The intimacy is staggering.

Where Springsteen’s Darkness on the Edge of Town and The River box sets traced branching paths—alternate takes, imagined roads not taken—this one focuses on distillation, on the process of carving away. Electric Nebraska, long whispered about in fan circles, is the clearest window into that process. The sessions play like sonic sketches: Springsteen on electric guitar and voice, Max Weinberg’s restless drums, Garry Tallent’s steady bass. It’s a fascinating mess, a blueprint for the Born in the U.S.A. sound before the anthems arrived. The songs toggle between grim ballads and breakneck rockers, their tonal whiplash reflecting an artist caught between austerity and grandeur.

And yet, much of it feels off, as if the electricity short-circuited the songs’ quiet dread. “Open All Night” and “Johnny 99,” normally wired with insomnia and desperation, here sound like a bar band’s last call warm-ups—fun, but emptied of menace. Even the early “Downbound Train,” with its churning rhythm and twisted bridge, comes across as unhinged rather than tragic. You can hear why Springsteen shelved it. What emerges is a portrait of a writer discovering, in real time, that rawness isn’t something you can recreate under fluorescent light.

For the faithful, the real reward lies in the transformations. “Child Bride,” the eerie skeleton that evolved into Born in the U.S.A.’s “Working on a Highway,” sounds like an exorcism caught on tape—its laughter and lust twisted into something ghastly. “Losin’ Kind,” a country lament whose ending trails off into silence, finally gets an official release after decades in bootleg limbo. And then there are two brand-new revelations: “On the Prowl” and “Gun in Every Home.” The former conjures a restless specter of early rock’n’roll, all slapback echo and haunted repetition; the latter paints a portrait of suburban dread so vivid it’s almost unbearable. When Springsteen mutters, “I don’t know what to do,” it lands not as resignation but prophecy.

The power of Nebraska has always been in its restraint, its willingness to sit in the dark without resolution. In any given song, Springsteen might inhabit the mind of a murderer, a fugitive, a man already halfway to hell. The line between sinner and survivor blurs. The expanded box doesn’t try to resolve that tension—it amplifies it. Even the archival material feels possessed by the same cold flame.

The accompanying booklet includes Springsteen’s handwritten notes to manager Jon Landau from January 1982, a document that reads like both confession and field report. He goes song by song, dissecting themes, hinting at arrangement tweaks, and, crucially, scribbling one unforgettable margin note next to “Born in the U.S.A.”: Might have potential. In that understatement lives the whole contradiction of the era—a songwriter lost in the fog, yet still tracing the faint glow of what would become his most misunderstood anthem.

What Nebraska 82: Expanded Edition ultimately offers is not closure but context: a clearer view of how chaos and clarity coexist in the act of creation. You can hear the struggle in his breath, the quiet terror of capturing something so personal it feels invasive. The lo-fi myth dissolves under scrutiny; what remains is intention, patience, faith. The music sounds better now not because it’s cleaner, but because the silence around it means more.

Springsteen once sang about the “magic in the night.” Nebraska 82 proves that magic was always there—it just happened when nobody else was watching.