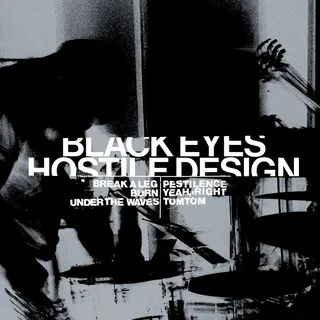

When Daniel Martin-McCormick screams, “Kill your shitty parents, let their blood flow free,” two minutes into “Burn,” the second track on Hostile Design, it lands like an invocation—not of shock, but of continuity. Two decades since their last album, the D.C. noise collective still wields fury like scripture. The difference now is how they frame it: not as youthful combustion, but as deliberate ritual. Hostile Design is an album born from the debris of old chaos, rebuilt with new architecture. It doesn’t just prove that Black Eyes can still ignite; it shows that they’ve learned how to burn with precision.

At the dawn of the millennium, Black Eyes seemed to erupt out of Washington, D.C. fully formed—an ecstatic tangle of dueling basslines, twin drum kits, shrieking saxophones, and incantatory vocals that sounded like political slogans spat through distortion. Their debut album was a weaponized collision of no wave and post-punk, a protest record disguised as an exorcism. Cough, their 2004 follow-up, dissolved structure entirely, transforming rage into something closer to transcendence. The music was violent but not cruel, communal but not comforting. When they disbanded before Cough’s release, it felt inevitable: You can only sustain that level of collapse for so long before it devours itself.

That’s why their 2023 reunion felt less like nostalgia than resurrection. The question wasn’t whether they could recapture their intensity, but whether they should. Punk reunions often chase their own ghosts, hollow imitations of past volatility. Hostile Design dodges that trap entirely. Rather than replicate, the band reimagines. They build space into their noise, inviting air, texture, and dub-style echoes to occupy what used to be pure density. The result is an album that feels heavy and hollow at once—a monument built from the same materials as before, but arranged to let the light leak through.

“Break a Leg,” the album’s opener, builds like a ritual. A low, rumbling bassline pulses beneath shuffling percussion; the saxophone creeps in like smoke before the whole track detonates. It’s a reminder that Black Eyes can still go nuclear when they want to, though now their explosions arrive with timing, not panic. On “Under the Waves,” a liquid bassline snakes through the mix, unbothered by a skronking sax solo that feels more meditative than manic. It’s one of the grooviest tracks they’ve ever recorded—proof that fury can dance, too. The closer, “TomTom,” drifts into dubby spaciousness, Hugh McElroy whispering in Haitian Creole as the band’s instruments echo into infinity. It feels less like a song than a séance.

If their early records were about collapsing boundaries, Hostile Design is about manipulating them. Half the tracks stretch past six minutes, using repetition and space to reframe their aggression. The production—humid with echo and delay—turns chaos into choreography. The record’s title feels literal: every shriek, every drum hit, every moment of feedback carefully placed within an intentionally hostile framework. The design here is both sonic and philosophical—a tension between precision and fury, control and surrender.

Lyrically, the band still aims their anger at the world’s cruelties. “Pestilence” seethes against genocide and the apathy that sustains it. “Burn”’s infamous line about parents reads not as cheap provocation but as generational indictment—a howl against those who sold out the future. Across the album, the band sings in four languages, widening their protest beyond geography. Black Eyes’ lyrics have always been fragmented, more impressionistic than declarative. But when Martin-McCormick and McElroy trade lines about “the spilled blood of slaughtered children,” the message is unmistakable: this is music for a world that hasn’t learned from its own collapse.

The interplay between rage and reflection makes Hostile Design more than a reunion—it’s an evolution. Where earlier Black Eyes records felt like detonations, this one feels like an aftershock measured in real time. The band no longer sounds like they’re tearing themselves apart; they sound like they’ve learned how to inhabit the wreckage. The record’s middle stretch—especially the twin highlights “Latency” and “Finger”—demonstrates this shift. “Latency” floats on delicate electronics that could have turned syrupy in less capable hands, but here they act as counterpoint, a momentary breath before the plunge. “Finger” dives back into dissonance, its cavernous reverb swallowing Martin-McCormick’s shouts until they dissolve into abstraction. In lesser bands, such tension between restraint and release might read as indecision; for Black Eyes, it’s a statement of survival.

The album’s most startling moment arrives midway through “Rest,” when glassy synths chime against a harpsichord-like melody that feels alien to the band’s history. It shouldn’t work—but it does. The juxtaposition captures the record’s ethos: beauty discovered through abrasion. Haino once said he sings to become one with someone outside himself; Martin-McCormick and McElroy seem to share that impulse. Their noise isn’t an escape from the world but an attempt to connect more deeply with it—to carve meaning from cacophony.

By the time the final echoes fade, Hostile Design has achieved something rare for a reunion record: it feels essential. Not because it reclaims the past, but because it understands how to outgrow it. Where Cough was disintegration, Hostile Design is reconstruction. The anger is still there—feral, uncontainable—but now it’s been honed into architecture. Black Eyes have built a cathedral out of their own ruins, and the echoes inside it sound like liberation