.webp/:/cr=t:0%25,l:0%25,w:100%25,h:100%25/rs=w:1280)

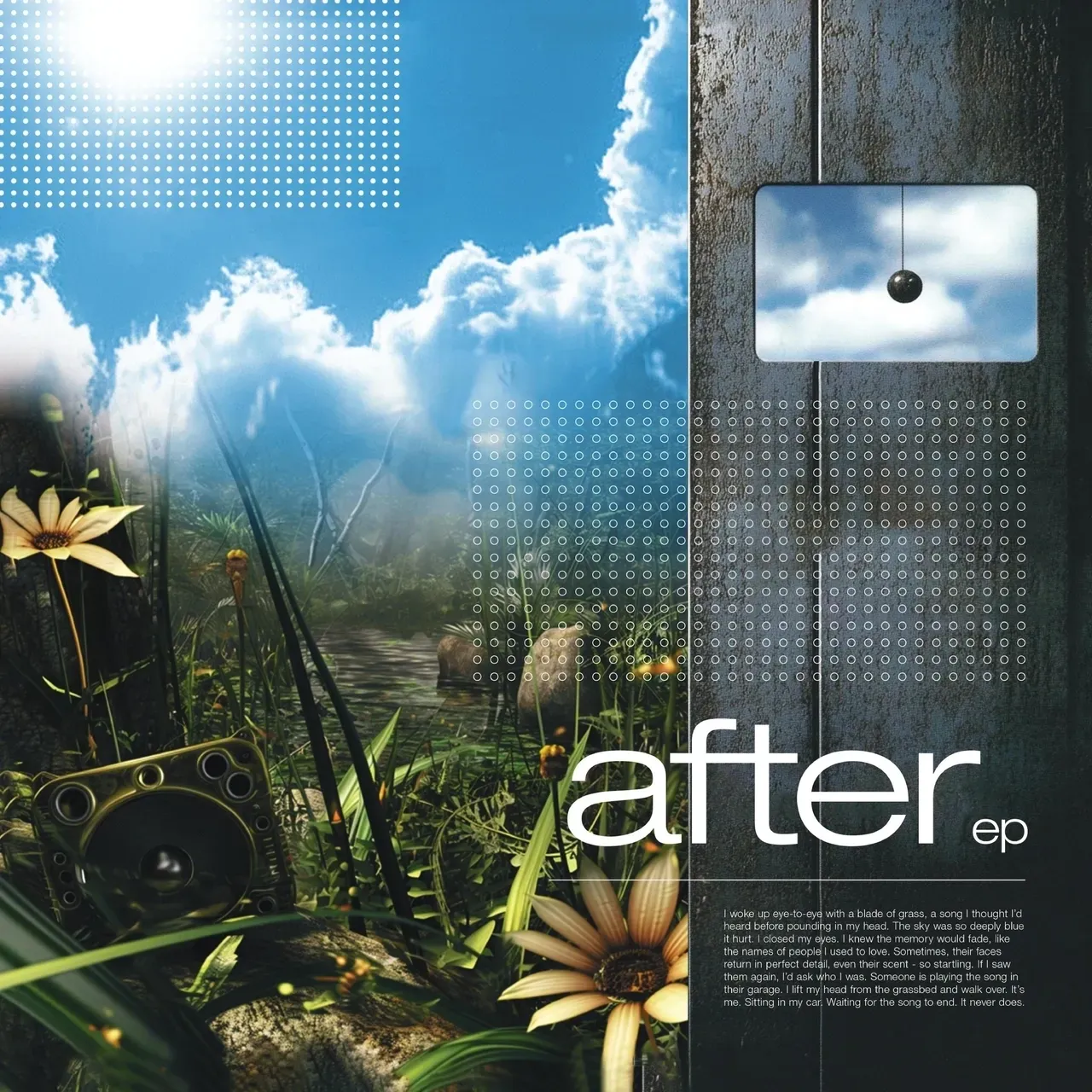

If you stumbled across L.A. duo After during your recent scroll through TikTok or Instagram, you might be surprised to learn that their two self-titled EPs materialized only this year. Vocalist Justine Dorsey and producer Graham Epstein—perpetually styled like they walked straight out of Frou Frou’s Details booklet—present themselves as Y2K apparitions beamed in from a frost-tipped 2003. But their immaculate cosplay is less reinvention than fastidious reenactment. Rather than teasing out the emotional textures buried in early-’00s radio pop, After treat that entire era like a perfectly preserved snow globe: shake it once, watch it sparkle, and hope no one notices there’s nothing inside.

Their opening tracks, “300 dreams” and “Deep Diving,” are near-identical exercises in breakbeat pop revivalism—museum-grade facsimiles of songs that once filled the airwaves while you waited for your mom to pick you up from school. Dorsey described “300 dreams” as her attempt at something “Coldplay-coded,” but the coding seems to stop at “Coldplay chord progression.” Over jittery breakbeats, she performs a feather-light Chris Martin impression, intoning vague uplift undercut by mood-board malaise. “Deep Diving” hits copy-paste, this time with lyrics that read like a stuck CD player—“the stones on the beach…the shells on the beach…”—before abruptly cutting out, as if the track gave up on finishing itself. These choices chip away at the illusion; nostalgia is a fragile drug, and After keep dropping the vial.

Elsewhere, the duo gesture toward emotional storytelling but rarely land on anything vivid. EP 2’s “Where we are now” echoes the soft ache of Frou Frou’s “Hear Me Out,” but substitutes its metaphorical delicacy for a circular platitude that evaporates upon contact. “Close your eyes,” a breathy, synth-lit ballad, imitates Speak for Yourself’s tender melodrama at only a fraction of its potency. The brilliance of Imogen Heap—the way she could scream “shut up” and whisper she’s “on your side” seconds later—came from emotional voltage. After’s performances, by comparison, are set to permanent screensaver mode, drifting over Epstein’s hushed, ROMpler-smoothed production like a hologram you can’t quite touch.

EP 1’s “Obvious” is pristine mall rock—glossy, tight, and engineered down to the smallest hi-hat. But what made early-’00s mall rock iconic was its attitude: bratty, earnest, clumsy, loud. Here, it’s all style, no pulse. Even the Vanessa Carlton-style staccato strings land less as inspiration than as mandatory nostalgic garnish, like a restaurant plating mint leaves on every dessert whether they make sense or not.

Great retro music never treats the past as a costume; it treats it as material. Artists like PC Music reanimated forgotten sonic artifacts to critique, celebrate, and destabilize pop culture all at once. Danny L Harle has transformed this sensibility into lush, maximalist pop that bridges eras rather than trapping itself inside one. But After aren’t interested in interpretation—they’re devotees of replication, apostles of anachronism without the self-awareness. A track like “Outbound,” a sugary pep-talk anthem built on promises of movie outings and park dates, embraces a kind of aggressively bright naivety that feels less nostalgic than delusional, especially in the aftermath of the very economic pressures this era’s optimism failed to foresee.

Beneath the shimmering Y2K varnish, After’s music offers little beyond the thrill of recognition. Maybe that’s enough for an algorithmic moment—a sonic filter you can apply to your life like a throwback Instagram preset. But once the sheen wears off, what remains is a revival with nothing to revive. Like Crystal Pepsi, it returns from the cultural vault with impeccable branding and no discernible flavor.