In a 2003 interview with CMJ New Music Monthly, Aesop Rock takes the scalpel to his own legend. The resulting portrait is less about mythmaking and more about entropy: a hyperactive brain tangled in its own machinery, an artist negotiating the friction between perception and reality. In his cluttered Brooklyn apartment—spent matchbooks, ashtrays spilling onto the floor, stray CDRs scattered across the carpet—Aes observes El-P and his publicist Teal tidying up what can’t be tidied. The scene reads like a mise-en-scène for neurosis: Aes, circling, ambivalent about fame, oscillating between grandiose claims of his records’ eternal significance and anxieties over the simplest perceptions of self. This was during the press cycle for Bazooka Tooth, the nervy, follow-up-slash-middle-finger to 2001’s Labor Days, which had finally propelled him into minor rap stardom. Critics hailed him a “genius,” but Aes cuts the fantasy short: “Look at my fucking crib. There’s Pepto Bismol spilled on the freaking coffee table.”

Born Ian Mathias Bavitz in 1976 in Suffolk County, New York, Aes grew up in a quiet household, the middle child between brothers Graham and Chris, often retreating into drawing. His visual art would eventually carry him to Boston University, where he earned a Certificate of Fine Arts in 1998. Rap was incidental, a curiosity more than an ambition. Early fandom for Run-DMC and the Beastie Boys did not predestine him for an underground canon; Aes’ creative DNA was as visual as it was verbal. When pressed on his notoriously dense lyrics, he’d shrug: “I just write about what I see and perform it with conviction. It’s mad obvious when cats act deeper than they really are, so it doesn’t make sense to do that.”

But the late ’90s underground wouldn’t leave Aes alone. As he built a buzz in New York’s subterranean rap circuits, the narrative around him hardened: mythic, quasi-prophetic, a lyrical savant sent to “redefine hip-hop.” He resisted. “All these subgenres are things that didn’t exist when I first started rapping,” he told CMJ. “Now it’s like ‘leader of the nation of avant-hop prog-rap’—I don’t even know what the fuck that means!” Lanky, pale, with a perpetually unkempt beard and exaggerated, almost comical eyes, Aes was the antithesis of the hip-hop archetype. On camera, he’s perpetually on edge, cigarettes in hand, baritone voice frayed by smoke, words hammered out over a thick Long Island accent. He raps in labyrinthine sentences, 50-cent words and ornate imagery stacked like Jenga, each line a cryptogram: “If this means anything at all anyway, it’s a riddle” (Nickel Plated Pockets, 2002).

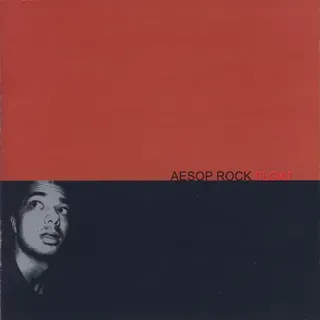

Aes emerged in a moment when East Coast hip-hop was experimenting with both cadence and abstraction. Nas and Big L expanded syllabic possibilities; Aceyalone and Company Flow filtered philosophy, sci-fi, and dystopia through the grind of braggadocio; Camp Lo invented entire dialects of slang. Blockhead, his frequent collaborator, recalls their first meeting: Aes resembled Saafir, the late Oakland MC whose Boxcar Sessions was a density machine, a neutron star of triple entendres. By 2000, with the release of Float, Aes had fully synthesized this underground ethos, arriving at a style that was equal parts cerebral dexterity and frenetic urgency. Float was not refinement; it was momentum crystallized.

Recorded largely on a Roland VS-880 workstation, with beats produced via ASR-10 samplers, the album brims with a ramshackle, immediate energy. Vocals tracked handheld on an SM-58 microphone, layers of ad-libs and overdubs collide like bees in a jar. There’s little breathing room; instrumental interludes like “Dinner With Blockhead” offer only brief respite, still stuffed with plucked bandoneons and breakbeat thrashes. Across tracks like “No Splash” (rain-streaked Gershwin jazz) and “Fascination” (’80s noir electro), Aes flexes internal rhymes, dense imagery, and erratic flows, demonstrating a restless intelligence that turns every verse into a microcosm of observation, anxiety, and humor:

“My tummy’s full of glass because I promised my friend I’d chew up the bottle if he truly drank the poison / I cherish the Ferris wheel’s revolutions not because the ride enthralls / But more simply to the fact that it still revolves.” (The Mayor and the Crook)

.webp/:/cr=t:0%25,l:0%25,w:100%25,h:100%25/rs=w:1280)

In “How to Be a Carpenter,” Aes offers a parable of artistic persistence, climbing tattered ladders toward the sun, cigarette alight: the image encapsulates a career spent mapping chaotic interiority onto language. Songs like “6B Panorama” prefigure later obsessions with place and hyper-specific detail; Float’s paranoid lyricism and rapid-fire cadences foreshadow the meticulous storytelling of Labor Days and Bazooka Tooth. The record feels like the blueprint for Aesop Rock’s oeuvre: an album where density is deliberate, complexity is joy, and the quotidian, bizarre, and cosmic coexist in baritone consonance. Float is not only the defining statement of Aesop Rock’s early career—it is the axis around which his subsequent innovations revolve, a document of a mind at perpetual motion, and a reminder that for him, hip-hop was never about convention, but about expansion.