In the slow, centerless world of Weirs, folk music moves like a dream—an ancient memory that leaps from mind to mind, echoing through time. The North Carolina collective treats the American songbook not as a sacred text, but as raw material: ballads, hymns, and standards are lovingly disassembled and spread across their workshop table, each fragment a gear in a homemade time machine. On their second album, Diamond Grove, simple melodies expand into hypnotic odysseys. Tape hiss, digital ghosts, and field recordings blend until the boundaries between past and present dissolve, as if history itself were being polished away with metamodern turpentine. What emerges feels like a haunting transmission from another dimension—familiar, but just out of reach.

At the album’s heart is Oliver Child-Lanning, whose fiddle-string tenor, equal parts Arthur Russell and Sam Amidon, guides Weirs’ spectral harmonies. The group began as a lockdown collaboration between Child-Lanning and Justin Morris of Sluice, resulting in their debut Prepare to Meet God—a project defined by its sense of isolation. On Diamond Grove, released via Dear Life Records, that disembodied spirit finds a body again. The music breathes, alive with jaw harps, turkey calls, pipes, and junk percussion—sounds that jostle playfully above rich layers of organ, strings, and voice. The band’s approach mirrors how we now hear the past: warped by memory, technology, and distance, yet still vividly human.

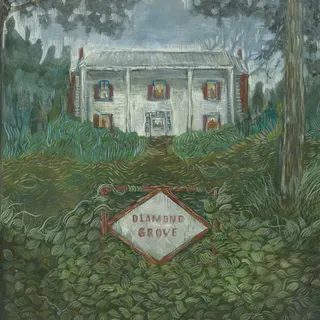

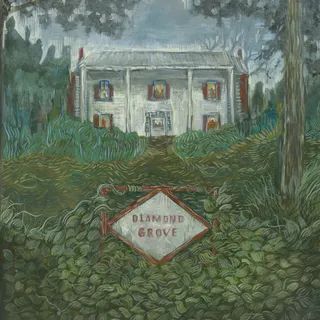

The album’s name honors Diamond Grove, a former Virginia dairy farm where Child-Lanning’s grandfather once lived. The nine musicians gathered there to record, drawing on the space’s own acoustic life—the creaking floors, the echoing silo, the chatter of birds and insects. The environment seeps into the music, giving the album its organic pulse and ghostly warmth. Field recordings of daily routines—cooking, cleaning, conversation—thread through the compositions, folding the domestic into the divine. The result feels less like an album and more like a living document, a folk archive vibrating with the energy of real time.

.webp/:/cr=t:0%25,l:0%25,w:100%25,h:100%25/rs=w:1280)

Weirs’ extended ensemble includes Libby Rodenbough of Mipso, along with members of Magic Tuber Stringband, whose own work similarly bends old-world sounds into surreal new forms. Together, they weave fiddles, cellos, banjos, harmoniums, and shape-note harmonies into glowing, prismatic drones. The reimagined spiritual “I Want to Die Easy” bridges the traditional and the transcendent—its close harmonies bloom into lush gospel layers that ripple into dissonance, evoking both the revival tent and the avant-garde studio.

Elsewhere, “Everlasting” mutates a hymn into a swarm of electroacoustic psychedelia, while “Doxology (I),” a pitch-shifted fragment based on a Sacred Harp tune, condenses devotional ecstasy into 72 seconds of radiant compression. The album’s centerpieces are two radically transformed English ballads—“Lord Randall” and “Lord Bateman”—the latter stretching to nearly 20 minutes of mesmerizing abstraction. It sounds like someone dragging a bag of wind chimes through a surrealist landscape, each clang and shimmer refracted into strange, liquid constellations.

What makes Diamond Grove so captivating is its patience. Weirs linger within every sound, letting each moment unfold at its own pace. Their music resists narrative urgency; instead, it thrives on the slow bloom of resonance and decay. In these deconstructed folk songs, the stories fade, but the feeling of continuity—the hum of tradition through time—remains.

With Diamond Grove, Weirs capture something profound: the sensation of the past flickering inside the present, not as nostalgia but as living current. Their music doesn’t reconstruct history—it communes with it, retrieving the warmth of human connection from the static of lost ages. The result is gorgeously strange, vividly alive, and unmistakably their own.