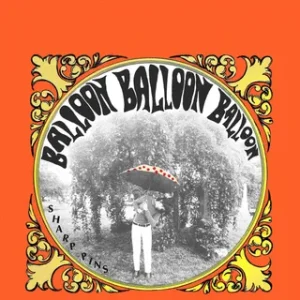

For the eternally beleaguered power-pop diehard, 2025 has felt like an improbable season of vindication. Paul McCartney is still out here filling stadiums with the ease of a man ordering tea; Sloan and Guided by Voices refuse to age in any direction but sideways; even the ecosystem of GBV-named bands continues mutating like affectionate bacteria. And somewhere in this surreal constellation, Martin Newell of the Cleaners From Venus is apparently broing down with The Rock. But nothing signals the renewed vitality of the three-chord true believer quite like the national ascent of Sharp Pins—Chicago’s Kai Slater, a songwriter young enough to slot into McCartney’s family tree several branches down. Once the quiet clearing house for the fragile tunes that didn’t fit Slater’s noisier trio Lifeguard, Sharp Pins became a full-blown event this year, thanks to the wide release of 2024’s Radio DDR and a coronation tour alongside indie lifers the Hard Quartet.

Where Radio DDR initially presented Slater as a studious graduate of the Robert Pollard academy—an industrious Midwestern tape-auteur sporting a hint of faux-Brit twang—the album never quite embraced Guided by Voices’ deliberate scruffiness. These weren’t sketches; they were polished bonsai-pop songs tended lovingly beneath a canopy of tape hiss. And beyond its barrage of earworms and hand-built harmonies, Radio DDR captured something more emotionally charged: a kid with limited tools conjuring the romance and kinetic possibility of a youthquake he wasn’t alive to witness. For a generation whose adolescence was siphoned away by a pandemic, whose adulthood feels prewritten by debt and doomscrolling, writing a silly love song can double as a quiet revolution.

But as the world tuned its dial to Radio DDR—and as Lifeguard dropped their own rattling 2025 firecracker, Ripped & Torn—Slater was already threading together Balloon Balloon Balloon, an album that preserves the hook density of its predecessor while letting his stranger impulses crawl into the sun. If Radio DDR unfurled like a greatest-hits playlist that played beautifully on shuffle, Balloon Balloon Balloon is almost theatrical in its pacing: 18 songs cleanly divided into three acts, each punctuated by a chaotic sound collage that behaves like the anti–palate cleanser—a dirt clod hurled between spoonfuls of honey. It’s an on-brand flex from a guy who also crafts a zine named after a Neu! song.

Throughout Balloon Balloon Balloon, Slater seesaws between the crystalline pop smarts of Radio DDR and the tape-warped mischief of his 2023 debut Turtle Rock. “I Could Find Out” masquerades as a Charmer until it gradually reveals itself as three songs stacked like geological strata, each layer exposed with the satisfaction of peeling labels off an old cassette. A noisier, more abrasive streak also creeps in: “I Don’t Adore-Youo” begins as a slack-rock shrug before it’s blitzed by a fuzz-caked solo and dubby, depth-charge drum effects that detonate every beat into a meteor impact.

But even as Slater wanders into the margins, the record keeps snapping back to pugilistic pop brilliance. “I Don’t Have the Heart” punches with pogo-stick precision; “Takes So Long” feels like a portal between British Invasion jangle and ’77 punk, collapsing two eras of teenage mania into one. The adventurousness widens the Sharp Pins palette, but the gravitational center remains unmistakable: Beatles-’65 optimism refracted through Beatles-’66 psychedelia, the sweet spot where winsome meets whimsical.

The opener “Popafangout” is a perfect thesis statement—jangle-drunk and irresistible, the kind of song whose nonsense title becomes an inescapable mantra. Before long you’ll be mutating it into private mishearings (“Papa Van Gogh,” “pop a Faygo”) without losing the melody’s tug. It’s the hallmark of great pop: turning silliness into something strangely transcendent.

Slater still borrows page layouts from Pollard, especially on starlit serenades like “Queen of Globe and Mirrors,” but the differences between their sensibilities now stand as clearly as the similarities. Consider the sly mirroring: the fifth track on Balloon Balloon Balloon, “(I Wanna) Be Your Girl,” is an upbeat acoustic charmer—mirroring Alien Lanes’ fifth track—but where Pollard would slip away after 90 seconds, Slater lets the sugar rush linger. And instead of cryptic collage-lyrics, he offers a sweetly earnest gender-flipped response to “I Wanna Be Your Boyfriend,” reframing club-show longing with soft-hearted clarity.

Slater writes songs the same way he makes zines: dispatches from his own small universe, smudged at the edges, imperfectly stapled, but packed with intention and affection. “Here I go/Fall in love again,” he sings on the song of the same name. On Balloon Balloon Balloon, that dizzy, earnest spark returns every two minutes or so—an initiation ritual for him, and a reminder for the rest of us that pop, at its best, makes falling in love feel permanently renewable.