December 03, 2025|Review

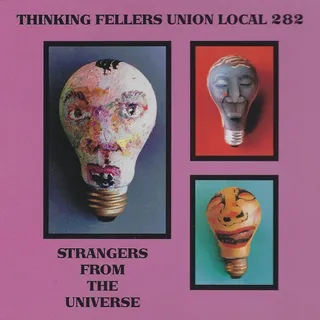

Anne Eickelberg knew the joke had calcified into something heavier. In April ’95, she cracked open her diary and test-drove a series of deliberately ridiculous acronyms—“Torrential Flood of Ugly Losers,” “Thwarting Forever Ubiquitous Lameness,” “Turds, Farts, and Uber-Logs”—as if trying to exorcise the burden of her band’s name by piling on something even more unwieldy. Thinking Fellers Union Local 282: a moniker that begins as a shrug and eventually sits on your shoulder like a jaded parrot. Seven months earlier, the Fellers had quietly delivered Strangers From the Universe, an album that opens with a punk-surrealist paean to a smug tortoise and ends with a folk-surrealist hum about the end of the species. Everything in between feels like flipping through someone else’s hallucination with the fast-forward button jammed.

Surrealism, yes—but also pranks, noise, sudden structural sweetness, and the kind of free-improv tornadoes that bowl you over before you can ask where the melody went. Five vocalists, three guitars, banjo, mandolin, Optigan, bass, drums: sometimes conversing, sometimes dog-piling. A lullaby that dissolves into a nightmare that dissolves into a joke you’re the last to get. This, somehow, was the band’s idea of going “commercial.”

The last of Eickelberg’s alternate acronyms—Tour Flunkies Under Live—reflected a grim reality. The Fellers had been tapped to open for Live, then in the process of lugging “Lightning Crashes” and its clenched-jaw piety toward chart dominance. The mismatch was biblical. The Fellers walked into vast arenas where basketballs hurled from the rafters curved past their heads like vengeful comets. One fan in the front row nearly dislocated his middle finger from overexerted hatred. The whole tour reads like a Bosch panel annotated in Sharpie. “It made it clear,” Eickelberg later said, “there was just no fucking way we were ever gonna get bigger than we were.”

By this point, the Fellers were deep into their fractal mid-career: Eickelberg on bass; Mark Davies, Brian Hageman, and Hugh Swarts tangling on guitars; Jay Paget drumming like a caffeinated Liebezeit. Everyone sang, everyone swapped instruments, everyone wrote. In the late ’80s they’d all lived together in a single Oakland house, bohemian-style, practicing until dawn, subsisting on cheap burgundy and twin big-band stations fuzzing from two radios simultaneously. The industry’s brief infatuation with “alternative rock” gave even the strangest acts a delusional sense of possibility. They opened for Nirvana once—technically, cosmically, enough to sustain hope.

Still, by the time Strangers materialized, they were four LPs deep, exhausted, and inching toward quitting. Matador had signed them, but the halo of prestige never quite translated to audiences. Their tour diaries—still archived in all their deadpan glory—chronicle bar-shows played for bartenders, half-empty guarantees, existential fatigue. After a yearlong hiatus and a move into a San Francisco practice space populated by junkies and squatters, something compelled them to try one last time.

Strangers From the Universe does not sound like a last-chance record; it sounds like five people attempting to reinvent how music works every four minutes. The “songs” outnumber the noise experiments slightly more than before, but they remain portals into a dream-logic where gravity flickers on and off. The mix is cleaner, which only highlights the band’s strangeness. Guitars scrape, banjos careen, basslines ping-pong off each other. They ask questions most bands would never think to ask: Why can’t mandolin be percussion? Why can’t two basses be the lead? Why can’t dissonance be lullaby?

“February” twists banjo filigrees around molten electric-guitar knots until they form some impossible hybrid of hoedown and no-wave. “Guillotine” nearly invents Animal Collective in slow motion, drifting from serene chime-work to childlike panic voices, as if the song is having a spiritual emergency. Even the miniature improvs—the affectionately named “Feller filler”—act as pressure valves, reminders of the deep improvisational engine beneath the surface. Skip them and you lose nothing; skip them and you miss everything.

The Fellers’ musicianship is the sort that critics call “accidental virtuosity”: nobody formally trained, everyone freakishly attuned. Their arrangements feel like architectural riddles—guitar lines and percussive scrapes slotting into impossible angles, each piece supporting another in a way that would collapse if tampered with. The Dead had their cosmic sprawl; the Fellers had their labyrinth, each riff a beam holding up a room you didn’t know existed.

The album’s peak—its cathedral—is “Cup of Dreams,” a seven-minute mosaic of toy-synth innocence, spy-movie bass, rainstorm ambience, and dream-pop shimmer. It unfurls like McCartney’s medley-brain run through a kaleidoscope: six miniature songs stitched together, each one beautiful in a way you almost forget as soon as it ends. You can imagine, for half a second, an alternate timeline in which the Fellers did get big—festival crowds swaying, lighters up, half-remembered words shouted into the void.

Yet Strangers is heavy with endings. “Socket” revisits a childhood near-death in jagged flashes. “Hundreds of Years” contrasts human pettiness with the patience of trees. “Cup of Dreams” erupts into a cleansing flood. “The Operation” turns surgical death into cosmic ascension, sung like a drunken hymn from some parallel afterlife.

“We were thinking about ending,” Hageman admitted. And in a sense, they were right: alternative rock’s so-called golden hour was collapsing in real time. Cobain was gone; the majors were pivoting toward grayscale post-grunge xeroxes. Live’s Throwing Copper was about to become the blueprint for the industry’s next, safer era. The Fellers, out of step with the world, were getting chased offstage so the professionals could get to work.

After one more year of touring and one more album—the equally dazzling I Hope It Lands—they drifted out of the career phase of the band. Their 2001 swan song, Bob Dinners and Larry Noodles Present Tubby Turdner’s Celebrity Avalanche, all chaotic title and soft heartbreak, opens with “91 Dodge Van,” a eulogy for the long, beautiful slog. They also included a track called “Boob Feeler.” Duality was the brand.

But Strangers ends with a last flash of tenderness: “Noble Experiment,” a waltz sung by Eickelberg that has become the band’s closest thing to a standard. A lullaby for humanity’s extinction, delivered with bizarre joy. If life is exhausting—if failure is inevitable—then perhaps ending becomes a kind of freedom. You evaporate into sparrows, into weeds breaking through concrete. You keep going, in some quieter form.

Thinking Fellers Union Local 282 never achieved the posthumous glow of Pavement or Duster; their audience remains the freaks, the obsessives, the listeners who enjoy the sensation of being lost. But Strangers From the Universe remains—like the trees that outlast us in “Hundreds of Years”—a monument to the uncharted. Strange, intricate, unmarketable, alive.

A record that shouldn’t exist, yet somehow does. A noble experiment that refuses to call it a day.