In the spring of 1994, months before Britpop hardened into a national pastime, Martin Carr stayed up all night with the Gallagher brothers and realized they were speaking an entirely different language. Oasis were still the new kids on Creation’s roster, opening for Carr’s band, the Boo Radleys, at a Glasgow festival. On paper, the groups were spiritual cousins—both Merseyside obsessives raised on the Beatles, both worshipping at the altar of Creation’s mythic indie empire, both young and hungry enough to believe the ’90s belonged to them. But when Carr finally met Liam and Noel, he found them impossible to decode.

Carr, then 25 and already the Boo Radleys’ chief architect, lived for deep musical digressions, bootleg Beatles tapes, and the micro-variations that separated one version of “Rain” from another. The Gallaghers lived for pints, chaos, and the incandescent thrill of being in a band. “I was into the Beatles as a progressive band,” Carr later said. “They were just: ‘No. Beatles. Mad for it.’” It was less a disagreement than a worldview divide—one that would end up mapping the fault line of British rock for the rest of the decade. Oasis embodied the fantasy of reliving the mid-’60s in real time; the Boo Radleys embodied what it meant to expand on that history rather than reenact it.

That distinction would become the Boo Radleys’ blessing and their curse. While Oasis stormed the world by adopting Beatles iconography wholesale—stealing chord changes, haircuts, and Lennon’s piano intros with unapologetic swagger—the Boos absorbed the Beatles’ restlessness instead. They had no talent for being reduced to a headline. Their lone Top 10 hit, the deliriously chipper “Wake Up Boo!,” got them lumped into Britpop’s parochial Class of ’95, much to Carr’s confusion. “I liked Blur,” he said, “but I must’ve missed the nationalist meeting.” The Boos wanted something stranger, more vaporous, more future-shocked than Britpop ever allowed.

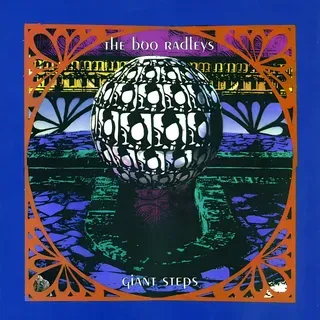

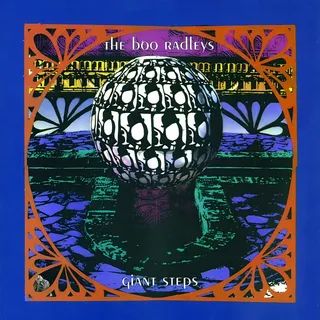

That vision crystallized on Giant Steps, their 1993 opus and one of the great “this should’ve changed everything” albums of the era. A psychedelic scrapbook of shoegaze, dub, avant-pop, and bubblegum melody, it imagines an alternate ’90s where genres didn’t splinter but melted together. Across 17 tracks, the Boos try on paranoid dub (“Upon 9th and Fairchild”), honeyed indie-pop confessional (“Wish I Was Skinny”), high-volume skronk (“Leaves and Sand”), sunset psychedelia (“Spun Around”), and Human League-coded anti-racist synth-pop (“Rodney King”), holding it all together with melodic intuition and curiosity that felt bottomless.

What’s astonishing is how coherent this kaleidoscope sounds. Carr—smoking Nepalese Temple Balls, dredging childhood memories, and dreaming of albums that felt like landscapes—imagined a record as expansive as Bitches Brew, as self-contained as the White Album, as labyrinthine as Daydream Nation. The Beatles whispers hide everywhere: a Dylan-ripped title here, Sice’s vocals recorded on a rooftop there, feedback crafted in homage to Hendrix’s “Star-Spangled Banner,” a “Hey Jude”-esque singalong blooming out of the gray. And when Sice sings about putting on the Beatles after a soul-flattening day at work, the song leaks a spontaneous “Yeah yeah yeah yeah!” from the right channel—a ghost of joy poking through the gloom.

This affinity wasn’t abstract. Carr and Sice grew up a river away from Liverpool, miming rock stardom with tennis rackets in Wallasey living rooms. Before the Boos formed in 1988, Carr logged a doomed stint in the Land Registry, drinking gin daily and fantasizing about a different life. Their early records had the charm and clatter of shoegaze imitators, but by the time they landed at Creation, they were mutating fast. 1992’s Everything’s Alright Forever still dreamt in fuzz, but with eccentricities that signaled where they were headed. Then came “Lazarus”—six minutes of dub sorcery and horn-blasted euphoria, their freak flag raised so high it blotted out the sun. Critics loved it; the charts did not. A familiar omen.

Creation insisted “Lazarus” appear on Giant Steps, and it sits there like a roadmap for everything that follows. Even the moments that should’ve flopped—shoegaze kids skanking on “Upon 9th and Fairchild,” the wind-tunnel psychedelia of “Leaves and Sand”—work because the Boos treated genre not as costume but as raw material. Their noise wasn’t a fortress, like MBV’s; it was communal, porous, flecked with brass, cello, woodwinds, and cheap Casio sighs. “Thinking of Ways” sounds like SMiLE reimagined by Yo La Tengo. “Barney (…and Me)” hides Wilsonian harmonies whispering “Faye… Dunaway!” in its a cappella break. “The White Noise Revisited” ends with a choir of friends chanting the record into light.

For all its experimentation, Giant Steps is an album about being young and already nostalgic for yourself. Carr’s songs sift through childhood fantasies, quarter-life panic, the ache of wanting to be better, thinner, happier, transformed. “Wish I Was Skinny” is the kind of brutally earnest yearning you only write before the world convinces you to hide your feelings. That transparency extended to Sice’s vocals—bright, open, McCartney-clean, a rarity in the muffled fog of early ’90s alternative rock.

You would think all this ambition, all this heart, would have propelled the Boos to the top. For a moment, the press believed it would. Giant Steps was Select’s Album of the Year. NME ranked it second. Melody Maker wondered aloud whether this was the band the world had been “praying for.” But Britain had made its choice. It wanted swagger and punch-ups, not studio hermits building psychedelic symphonies. Oasis sold 440,000 copies of Definitely Maybe in four months. Giant Steps sold 60,000. One band bankrolled Creation; the other endangered it.

The Boos survived long enough to make their expected mainstream bid—1995’s Wake Up!—but success felt hollow. Carr had believed that being a pop star meant you became someone else. Turns out you stay you, just more tired. Their next album, C’mon Kids, was a snarling rejection of their newfound sunshine, and it lost them 100,000 fans. By 1999, the Boo Radleys were done, half remembered and half misunderstood—a cult band with a Top 10 albatross.

But Giant Steps remains, humming with secrets. Listen closely and it reveals new ones every time: backmasked voices whispering “Boo be with you,” strange choral samples flashing like apparitions, unearthed Easter eggs and inside jokes hidden in the stereo field. It’s an album that feels alive, unpredictable, and full of the sense that the ’90s could have unfolded in a completely different way.

A decade defined by genre wars and media-manufactured scenes couldn’t contain the Boo Radleys. But Giant Steps still points to the space between youthful yearning and adult malaise—the exact frequency where noise, melody, and psychedelia collide into revelation.