A woman lives alone in a garden enclosed by towering stone walls. Moss and lichen creep across the cobblestones like the skin and hair of some ancient being. The air smells of damp rock and memory. Everything inside the garden feels old, and even new things—flowers, leaves, the glint of water—are quickly aged by the stillness that hangs over it. No one can enter, and she cannot leave.

Sometimes, through narrow cracks in the wall, she glimpses a shadow passing by. She wonders who it is, what life might be like if they were together inside this sealed world. When the wind blows through the openings, she mistakes its murmur for a voice calling to her in a strange, indecipherable tongue. She aches to know whoever it is, but she can only know what she imagines—her own projections, refracted and distorted. In those shards of fantasy, she sees both the stranger and herself, flickering between presence and absence like reflections in broken glass.

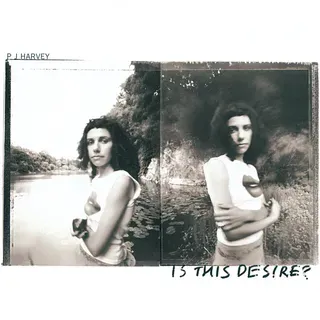

Every song on PJ Harvey’s Is This Desire? feels like it unfolds in that same walled garden. Each one is a small world of yearning, self-containment, and haunting. They move in circles, loops that never quite break. These are songs that end where they begin, cycling through verse and chorus like a ritual repeated daily. Their progress is less forward motion than emotional weather—shifts in pressure and temperature, waves of intensity and retreat. Desire dries up in the winter, then blooms again in spring. The singers in these songs are trapped in their longings, forever asking the same silent question: Here I am. Can’t you see me? Don’t you know who I am?

This was not Harvey’s first encounter with desire, nor her first time wrestling with the body and the spirit as warring forces. On her early albums—Dry (1992) and Rid of Me (1993)—desire was violent and elemental. Love came with teeth. She emerged from those records wild-eyed, screaming, sometimes covered in metaphorical blood. That energy climaxed on To Bring You My Love (1995), where she took on the persona of a red-dressed devil, a creature of temptation and power. She was both the seducer and the seduced, a woman who could summon and destroy with a whisper. “I was quite lost as a person then,” Harvey reflected later. “Rather than it being a mask, it was an experiment, a stage I needed to go through.”

Is This Desire? (1998) marks the end of that experiment—and paradoxically, it’s also the album most populated by masks. Every song is a story told through another voice. But where earlier Harveys wielded power, these new voices are powerless. The women in Is This Desire? have no control over their lives or the people they love. They are moved by longing alone, driven by hunger so strong it consumes the self.

The album opens with “Angelene,” its plainspoken melancholy setting the tone. “My first name Angelene, prettiest mess you’ve ever seen,” Harvey sings softly, almost without affect. Her voice sounds newly unguarded—neither feral nor theatrical. She had taken vocal lessons before recording the album, and the shift is unmistakable. “For the first time in my life I’m singing with a voice that is my own,” she told The Irish Times. “I’m not wearing a mask or playing a part.” The song’s uneasy guitar chords waver, restless beneath her words, while the drums roll in like a distant tide. Angelene dreams of a man far away, a love that might redeem her from being an object of desire and allow her to desire freely in return. But her dreaming is only a reprieve from the monotony of her reality, from the men who visit her bed without ever seeing her face. The imagined man, the ideal, remains just that—unreachable, unsullied by life.

At the time, Harvey confessed, “One of my dreams is to be a writer—not just a songwriter, but a short story writer.” The songs on Is This Desire? carry the same quiet discipline and compression of short fiction. She had been reading Raymond Carver, J.D. Salinger, and Flannery O’Connor—writers who specialized in small, devastating portraits of people trapped by their own natures. Each of Harvey’s narrators is similarly caught: imprisoned by desire, fear, or faith. As she once said of O’Connor, “Everyone in her stories is doomed to be themselves.”

O’Connor’s influence is explicit. Two songs on Is This Desire? reimagine her stories, most strikingly “Joy,” which revisits the protagonist of Good Country People: an unmarried woman with a prosthetic leg who studies philosophy but lives at home, bound by her own intellect and bitterness. She prides herself on her detachment, believing she sees through the illusions of love and faith. But when a traveling Bible salesman appears—apparently innocent, perhaps sincere—she’s briefly undone. When he betrays her, stealing her leg and her dignity, she’s left with nothing. Harvey’s “Joy” captures that same tragic irony: a woman who believes in nothing but ends up believing too much in something that can’t save her. Like many of the women on Is This Desire?, she’s undone by hope itself—by faith in what refuses to arrive.

The world of the album carries the same thick, humid mood as O’Connor’s South, though Harvey’s landscapes are English and spiritual rather than geographical. Even when a song is quiet, its atmosphere feels heavy and dense. The air hums with sound—buzzing insects, whispered winds, the faint wail of sirens. Every movement leaves an imprint. The arrangements are skeletal but alive, and each instrument acts as an extension of character. On “A Perfect Day Elise,” for instance, the percussion sounds like fists on a hotel door, as if reality were intruding on an affair that, for one of the lovers, is sacred rather than physical. The synth line in “Electric Light” hums like a fluorescent bulb in a morgue, turning desire into something spectral and unnerving. It’s a love song for someone who might already be dead.

When I listen to Is This Desire? now, I sometimes imagine “Electric Light” as the aftermath of “Elise”—that the man’s obsession becomes so consuming he destroys what he worships, freezing her forever in perfection. It’s a dark reading, perhaps too dark, but Harvey’s storytelling invites it. The songs echo one another like dream fragments—repeating names, symbols, winds. In “The Wind,” a woman named Catherine climbs to the tops of hills to make whale sounds into the air, seeking communion with something divine. Later, in “Catherine,” she reappears in another’s jealous lament: “I envy the wind, your hair riding over.” Desire moves from spiritual to physical, from adoration to resentment.

Harvey’s sound at this time was in flux—halfway between the rough edges of her early records and the clean storytelling of her later work. Her collaboration with Tricky on “Broken Homes” earlier that year seeped into the record’s texture. Tricky’s approach—dark, slow, unpredictable—taught her to let songs breathe in their discomfort. “He’s not afraid to try anything,” she said admiringly. “No matter how revolting or uncommercial. He follows his own path.” That ethos runs through Is This Desire?, particularly in “My Beautiful Leah” and “Joy,” where songs feel submerged, as if recorded underwater. The women in these songs are half-drowned in their own emotions, unable to lift themselves from the mud. Listening feels like overhearing their inner monologues—snatches of feeling, fragments of lives in collapse.

The album feels, in many ways, like a series of field recordings of the soul. Harvey captures emotions at their rawest—loneliness, longing, spiritual exhaustion. You can almost hear the grind of teeth, the slow pulse of blood, the ache of wanting something that can’t exist. Her characters are all the same person, in different guises: alone, yearning, on the verge of disappearance.

And then, at the end, Is This Desire? offers a kind of fragile grace. The title track introduces two people—Joe and Dawn—who seem to have found each other at last. They move together through a stripped-down landscape: sun rising, sun setting, warmth and coolness, fire and rest. For the first time, there’s no tension between them. Yet even in that peace, a question lingers in the air: “Is this desire? Enough, enough to lift us higher?”

The question reaches beyond love. It’s about the human impulse to want—to chase meaning, intimacy, transcendence—and the inevitable emptiness that follows when we find it. If longing gives shape to our lives, what happens when the longing ends?

For Harvey, the answer is neither resolution nor despair. It’s simply acknowledgment: desire itself is the force that keeps us alive, the restless current under everything we do. Is This Desire? is her most introspective, most haunted work, an album where stories fold in on themselves and people vanish into the very emotions that define them. Like the woman in her walled garden, Harvey’s characters never escape—but in their endless circling, they find something almost holy: the beauty of wanting what can never be had.