Before Tom Jenkinson became Squarepusher—the mercurial bass virtuoso who turned jungle into something resembling jazz calculus—he was just a kid in Essex chasing the afterglow of rave. Stereotype, recorded over two frenzied weeks in July 1994, captures that moment with disarming clarity. Holed up in a friend’s parents’ house at the end of a sleepy train line, Jenkinson turned suburbia into a micro–illegal rave, fuelled by Stella and teenage zeal. Tapes ran constantly. People drifted in and out. And amid the chaos, he cobbled together what would become the rough blueprint for one of electronic music’s strangest, most restless minds.

That energy explodes on “Whooshki,” a 16-minute acid-house sugar rush that starts like a bedroom experiment and spirals into full-blown delirium. The track’s four-to-the-floor pulse and escalating synth delirium sound like someone discovering freedom for the first time—dance music without structure, reason, or restraint. It’s proto–Squarepusher in all the right ways: too long, too loud, and completely alive. The jazz-like breakbeats and hyperkinetic drum programming that would later define him are nowhere to be found; instead, Stereotype bows at the altar of Aphex Twin’s Analogue Bubblebath, early Autechre, and the rough-edged euphoria of breakbeat hardcore. It’s less about invention than devotion—an artist teaching himself by imitation, turning the sounds he adored into his own sloppy, beautiful noise.

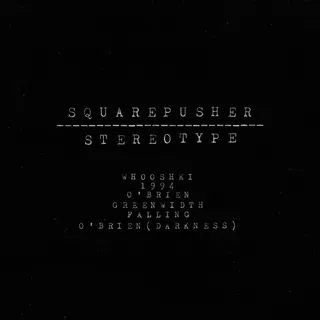

Pressed as a single 12″ with an absurdly long first side, Stereotype was destined to sound bad—muddy, thin, bassless. But that imperfection only adds to its charm. Warp’s reissue paints it as some “lost Squarepusher album,” though that’s generous. Even his earliest official records, like Conumber EP, already showed more finesse and wit. Still, there’s something intoxicating about the unfiltered joy here. “Whooshki” prefigures the ecstatic acid meltdowns of Roy of the Ravers by decades, while “1994” bridges the gap between rave euphoria and the drill’n’bass madness of Feed Me Weird Things. It’s the sound of someone tumbling toward their own identity without realizing it.

“O’Brien” digs into the darker corners of early UK hardcore, flipping between frantic breakbeats and halftime grooves like a DJ too restless to stick with one BPM. You can almost hear the rhythmic genius incubating, hidden inside the clatter. Elsewhere, “Greenwidth” and the remaining techno sketches feel like exercises—competent, occasionally hypnotic, but lacking the spark of the longer jams. Even then, hints of Jenkinson’s future obsessions peek through: an ear for harmonic complexity, a fascination with sonic density, and a sense that dance music could exist equally well in a bedroom as it could on a dancefloor.

As a historical document, Stereotype isn’t essential so much as endearing. It’s the sound of potential crackling at the edges of a DAT tape. Long before Squarepusher turned basslines into math problems or blurred IDM with free jazz, he was just another kid trying to capture the rush of a night that never seemed to end. What makes Stereotype so charming is its lack of self-awareness: no label deadlines, no scene politics, just an artist recording because it felt good. It’s the rare artifact of electronic innocence, made before skill turned to obsession, before rave ecstasy gave way to existential dread.

In the grand arc of Jenkinson’s career, Stereotype is a sketchbook—a messy, glowing footnote from the summer before Squarepusher became Squarepusher. But in its naivety, you can already hear the restlessness that would define him: the kid in Essex with no bedtime, turning sleep deprivation and cheap lager into transcendence.